Before the end of World War II and the fall of Mussolini’s Fascist regime, a different genre of Italian cinema emerged called Neorealism. The movement began in 1942 and took off in 1943. When the war ended, Italy found itself on its knees, after years or war, economic depression and hardship: neorealism was a reflection of this time. With its depiction of post-war Italy, the genre would dominate Italian cinema for almost ten years, as well as influence film styles throughout the world. Neorealism was a blend of traditional and new techniques, largely shaped by the war and its aftermath.

A relatively small number of film makers embraced the genre and most of them worked on each other’s movies. Italian neorealism’s masters were, without a doubt, Michelangelo Antonioni, Gianni Puccini, Giuseppe de Santis, Vittorio de Sica, Federico Fellini, Roberto Rossellini, Luchino Visconti, and Cesare Zavattini. The most recognizable of these names are Fellini and Rossellini, who co-wrote Roma, Città Aperta (Rome, Open City), directed by Rossellini in 1945. It is often thought to be the first and the most influential Neorealist film of all times.

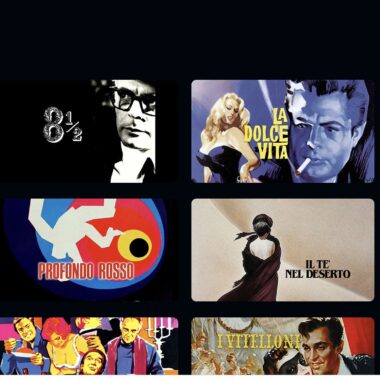

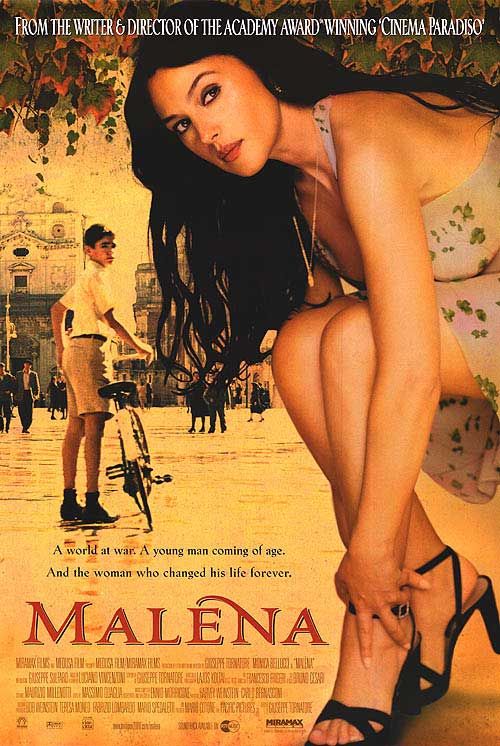

Long after the genre had declined Fellini went onto create wildly popular and surrealist films such as La Dolce Vita, 8 ½ , Amarcord and others.

One of the common desires of Neorealist film makers was to show the reality of life in Italy after World War II, and that reality was harsh for many reasons, most of them having to do with the war itself.

Most of Northern Italy was occupied by foreign troops until 1943, and the majority of the Italian territory was bombed throughout the conflict. Rome bore the brunt of the bombings on a number of occasions, and in 1943 was occupied by the Nazis. After the war the entire country, particularly the cities, were in shambles physically and economically. Poverty, unemployment, and anger were part of everyday life.

Many Italians felt despair both at their current circumstances and at the lack of opportunity for any sort of improvement in their lives, and Neorealist films captured this despair, in particular the feeling that the future looked more bleak than hopeful for many. In fact another common characteristic of these films was an unhappy ending. There would be no easy resolution or safe journey toward stability and prosperity for Italians and the films reflected this in stunning storytelling.

Scene from I Vitelloni, directed by Federico Fellini, with Alberto Sordi.

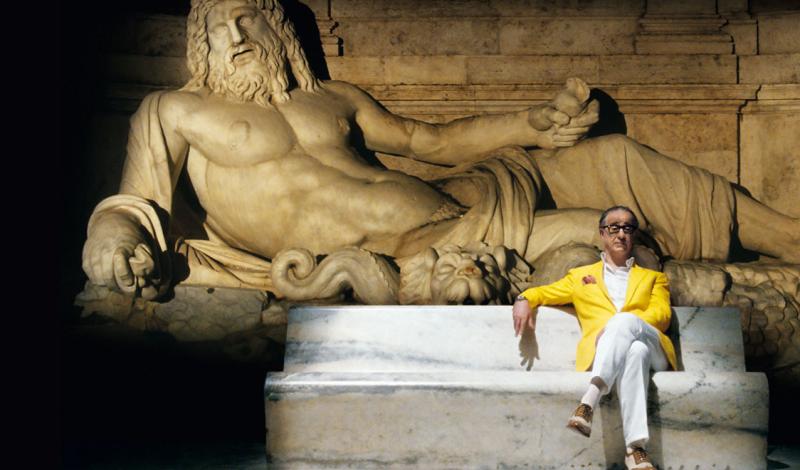

An important feature of neorealist films was the beauty and contrast of the images themselves.

Filmed in black and white these films have a haunting quality, with deep shadows and sharp edges echoing not only the harshness of life during the post-war years, but the emotions of the characters themselves. The stories often took place against the backdrop of a once-glorious empire. In Ladri di Biciclette (Bicycle Thieves) for example, a film by Vittorio de Sica, the bombed out areas of Rome are filmed against intact ancient monuments and crumbling walls stand in contrast to 1000 year old statues. Ladri di biciclette is probably the best known of all neorealist movies, at least by the larger public. In it all the characteristics of the genre are on display in a tightly woven story that leaves viewers on the edge of their seats, wrung out emotionally, and with an immense appreciation not only for the film maker but for the non-actors who so brilliantly inhabited the characters and their plights.

In fact one of the most innovative and exciting characteristics of Neorealism was its frequent use of non-actors in roles and leading roles. Brilliant performances by everyday Italians contributed to Neorealism’s realistic feel, as did the practice of shooting on location outdoors and in restaurants, businesses, and residential buildings.

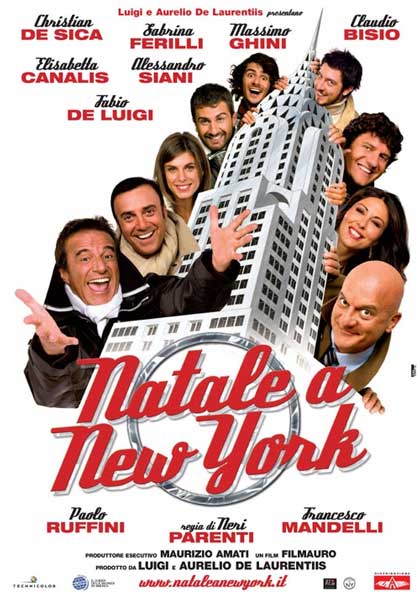

Other important titles in the genre are Sciuscià (Vittorio De Sica, 1946), Paisà (Roberto Rossellini, 1946), Germania, Anno Zero (Roberto Rossellini, 1948), La Terra Trema (Luchino Visconti, 1948), Riso Amaro (Giuseppe De Santis, 1949), Stromboli (Roberto Rossellini, 1950), Bellissima (Luchino Visconti, 1951), and I Vitelloni (Federico Fellini, 1953).

Despite the inclusion of I Vitelloni, in 1953, on critics’ lists, the Neorealist movement essentially ended in 1952 with the release of Vittorio de Sica’s Umberto D. Italian economic circumstances started to improve, the country was being rebuilt, and many Italians began to look toward happy themes and different film styles. As American film became popular a new Italian style emerged.

Neorealism as an Italian film style may have had a short reign, but its influence spread throughout the world. Echoes can be found in American Film Noir of the late 1940s and early 1950s, as well as in the 1950s development of French New Wave. Neorealism spoke to the world and continues to speak in haunting images and an authentic voice to tell the story of an entire country’s fight to return itself.