The so-called B movies of 1960s and 1970s Italian cinema have recently seen a revival, thanks largely to Quentin Tarantino and our culture’s post-modern tendency of digging out all that is old – the trashier the better – and make it new again.

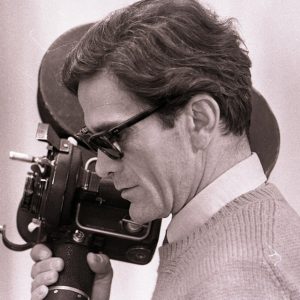

In the 1980s, when the future director of Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction was still working in a video store, he stumbled upon a number of films by the Italian director Fernando Di Leo. How those movies made it to a video store in Santa Monica in the middle of the 1980s remains a mystery, as by then Di Leo was a forgotten figure of Italian cinema. The director’s early 1970s thrillers had slipped into obscurity and his career had met a premature ending. It was a sheer stroke of luck that Tarantino discovered Di Leo’s work, which would go a long way to inspiring Tarantino’s own unique, brash and, yes, often times trashy style.

This episode is testament to the underground but steady growth of admiration for this genre of 60s and 70s cinema. Though the work of filmmakers such as Di Leo was regarded with contempt by the Italian filmgoing audience, his films and others like them were far more popular and readily available in the UK and US. This phenomenon shouldn’t take anyone by surprise: every film culture has its hidden treasures that only outsiders seem to value. In Britain, for example, Hammer Studios horror movies by Terence Fisher and John Gilling, completely overlooked by local critics, have been praised as masterpieces by Martin Scorsese.

The Italian-American director believes that one of the great paradoxes about B-movies is that they “are freer and more conducive to experimenting and innovating” than A-pictures. In addition, the development of Italian cinema from the 1930s onward happened as a result of an underground cadre of directors and craftsmen who embraced “low practices” in their film-making and so invented the first true Italian genre cinema.

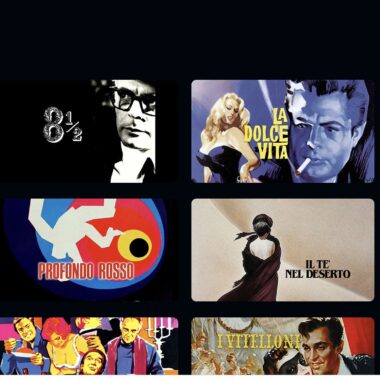

So, with the prestigious blessings of two incredibly talented filmmakers, let’s have a look at the wonderful world of Italian B movies of the ’60s and ’70s. First of all, since these films constitute the main bulk of Italian genre cinema, let’s define them. First, we have the cops and robbers genre, in fashion in the 1970s in the US too, craftily created by the above mentioned Fernando Di Leo and by another gifted director, Steno (Stefano Vanzina). The other main genre explored by Italian filmmakers of the time was thriller-horror, especially by the directors Mario Bava and Riccardo Freda.

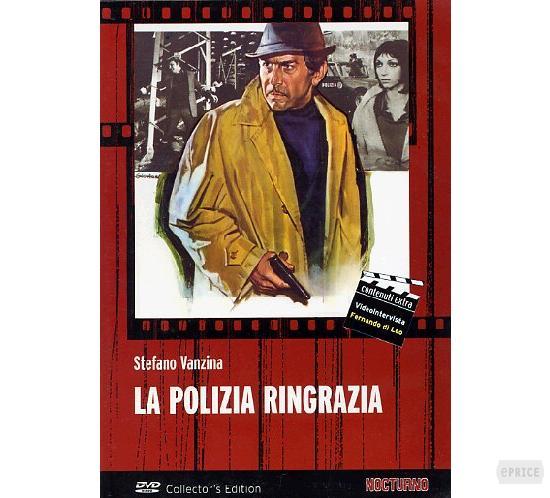

Cops and Robbers

The ’70s can be considered the golden age of the Cops and robbers genre in Italy, the way having been paved by the success of The Enforcers (La polizia ringrazia -1972), the only film made by the great Steno under his real name, Stefano Vanzina. The winning element of this movie was that it craftily crossed Italian “political” cinema (i.e. that of Damiano Damiani) with American action movies like William Friedkin’s The French Connection (1971) and Dirty Harry by Don Siegel. These two films – together with the later Death Wish (1974) by Michael Winner – can be considered the most obvious sources of inspiration for the Italian cops and robbers movies.

Condemned by critics of the time as crude and reactionary, these Italian films featured fast-paced plots and lots of action scenes. Generally, actual content wasn’t central and the message of “law and order” had only the purpose of providing a motivation for characters’ actions.

“Il boss” by Ferdinando di Leo

As already pointed out, the king of Italian cops and robbers was Fernando Di Leo: his movies were characterized by very peculiar poetic values, yet were also influenced by great writers like Melville and Siegel. The Boys who Slaughter (I ragazzi del massacro – 1969) marks his first collaboration with the Italian crime novelist Giorgio Scerbanenco with whom he worked again for the amazing Caliber 9 (Milano calibro 9 – 1972), the prototypical Italian noir movie, brilliantly combining roughness and pessimism in a dark tale of the criminal world.

Tarantino’s favorite Di Leo film of all time is Black Kingpin (La mala ordina – 1972), yet another movie that draws on a Scerbanenco novel, the story of a pimp unwittingly caught up in a diabolical vortex. The ultra-violent Murder Inferno (Il boss – 1972) closes this style in a trilogy dedicated to the “underworld” that has no equal in terms of pace and power in the history of Italian cinema.

Thriller – Horror

At the beginning of the 1960s Italy demonstrated an increasing interest in horror, a genre that had until then enjoyed only marginal popularity, possibly because Italian artistic and literary tradition lacked a figure like Bosch or Edgar Allan Poe. Though admittedly owing a lot to British canons of horror, Italian cinema possessed an original fil rouge: the central role of a fiendish female figure, both in the most classic portrayals (witches) and in more fantastically hybrid inventions (the vampire woman). This distinguishing feature is clear in the works of the most significant Italian directors of the horror-thriller genre such as Lucio Fulci, Riccardo Freda, Mario Bava and his internationally well-known “grandson” Dario Argento. This fiendish female is so pervasive through the ’60s and ’70s to be considered by movie critics as the founding core of a veritable theory of gynophobia.

Each of these well known Italian directors had his own unique defining characteristics. Freda, for example, in The Terror of Dr.Hichcock (L’orribile segreto del Dr. Hichcock – 1962) and The Spectre (Lo spettro – 1963), introduced a concept of horror spawned not by supernatural beings, but by human evil in a visual frenzy punctuated by necrophilic pulsations and sexual deviancy. Mario Bava, instead, right from his brilliant debut, Revenge of the Vampire (La maschera del demonio – 1960), focused his attention on figurative aspects and composition, the plot being a mere canvas for displaying his visionary talent.

In essence, though Italian B movies have been regarded by Italian critics and audience members alike as trashy byproducts of the cinema industry, thanks to their almost subversive strength and the sometimes ruthless but constant drive toward innovation, they constitute the steady and fertile ground where many great directors throughout the world have grown their cinematographic imaginary.

B movies’ freedom from artistic chains imposed by the great majors, its ability to be more daring in its content, and its typically low budgets which initiated new and inventive technical solutions to filming, can be regarded as sources of inspiration by those directors who were looking – and continue to search – for a fresh perspective on cinema. The great importance and vitality of this so called second rate cinema continues today, as filmmakers throughout the world find inspiration and ongoing relevance in these early B movies.

By Carlotta Scarlata