Like many other countries, the first films Italy produced were documentaries. Unlike today’s, they were only a few seconds long and filmed with a simple camera; the subject matter was the news and celebrities of their time, mostly kings, emperors and popes. An early pioneer was Filoteo Alberini, an ex-cartographer of the Military Geographic Institute of Florence.

The first Italian movie whose title is known is dated 1896 and tells the visit of the King and Queen in Florence. Unfortunately, most of the film has been lost; the fragments we still have traces of today show Pope Leo XIII going to pray in the Vatican gardens and turning to the camera for what is the first papal blessing filmed.

Though cinema in Italy has existed since the days of the Lumiere Brothers, with movie theatres operating since 1896, we can properly speak of the birth of the Italian film industry between 1903 and 1909, culminating with a period of glory in 1914. At that time, Italy was at the cutting edge in movie production and storytelling, and possibly the invention of the feature film as we know it today is to be credited to those early Italian screenwriters and directors.

The first Italian ‘Hollywoods’ were Florence and Turin.

Starting in 1903, thanks to a belief in the economic gains that the new entertainment medium seemed to provide, several movie production companies were started in major cities. Turin was the top production center in Italy with five production companies: Ambrosio Film, Eagle Films, Itala Film, Pasquali Film, and Savoy. In Rome, Cines Productions, Gladiator Film,Medusa Film, and Film Renaissance operated. However, the best equipped studios of the time were in Milan, built by the producer Luca Comerio who founded a company production with his name, now called Milano Film. This was soon followed by the emergence of other companies like Fortuna Films, Genial Film, Proteus Film, and Rosa Film. In Naples several film companies arose, three of which became of great importance: Lombardo Film, Napoli Film and Film Partenope.

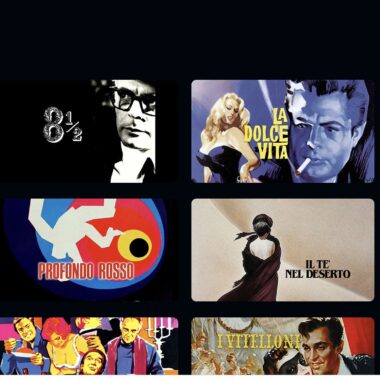

The first films were based on the Italian dramatic tradition. Starting in 1905, the Roman Cines production house produced a genre that made the fortune of Italian filmmakers and was exported all over the world with great success: the historical costume film (later called peplum). The first of such movies was The Fall of Rome, directed by Filoteo Alberini; it was a work of about 15 minutes, innovative in content but still traditional in technique, and was composed of a series of animated pictures inspired directly by the art world, particularly by the works of the painter Michele Cammarano. Quo Vadis? was produced in 1912 as was The Jerusalem Delivered, both by Enrico Guazzoni.

In Torino, Film Ambrosio, driven by the success of these movies, produced Mario Caserini’s The Last Days of Pompeii in 1913. It was a blockbuster with great visual effects for the time that recreated the volcanic eruption itself, with crowd scenes and an atmosphere of terror. The film is regarded as the father of the catastrophic genre and it was composed, too, by a series of animated pictures without editing.

Following this movie’s success many other historical movies were produced, basically retelling every major story of ancient Rome and the Italian Renaissance, many with mythological themes. The success of the French art film (a movement begun in 1908) pushed the Italians to emulate this form of cinema — cultured, and spectacularly refined. In particular, the Turin-based Film Itala, owned by Giovanni Pastrone, produced a series of art movies beginning in 1910 with the film The Fall of Troy. In 1911 Milan Films produced the first European film of great literary and artistic value, Hell, followed the same year by Velletri, produced by the competitor Helios Film.

Movies continued to be strongly influenced by theatrical settings, with long, fixed shots in medium to long range distance, just as if the screen was a theatre stage viewed from the audience’s point of view. Story length become longer, reaching and some times exceeding ten minutes.

Meanwhile, Giovanni Pastrone, galvanized by the success of his Fall of Troy, began producing a more ambitious movie named Cabiria. It was slated for a then unheard-of length of over two and a half hours, with spectacular settings derived from the tradition of the most spectacular productions of opera. His most important innovation was the decision to forego the fixed single camera and instead use numerous cameras and offer different views within the same scene.

This marked a breakthrough in movie technique. For this film he chose some of the most important representatives of the cultural scene of the time as partners, men such as Gabriele D’Annunzio and Ildebrando Pizzetti. Cabiria was shown in cinemas in 1914 and was an instant hit. It changed forever the language of movies and attracted the interest of Americans, influencing even the legendary David W. Griffith.

Historical and mythological movies were only two of the many being produced at the time. Comedies were also produced in large numbers and with good success. Pioneers of Italian comedies, however, were foreign actors such as: the Frenchman André Deed who played the character of Cretinetti, a prankster, drunkard and womanizer; the Spaniard Marcel Fabre and his character Robinet; another Frenchman, Raymond Dandy, with his Kri Kri character; and the Franco-Italian Ferdinand Guillaume known for his interpretation of Polidoro, a naive character halfway between man and child. Guillaume played Pinocchio in 1911 as well.

Following their examples, Italian comedians rose to the challenge and began bringing their own characters to the silver screen. Among them was Lea Giunchi, the first female comedian of Italian movies.

In 1914 another genre was born, the society drama, often inspired by works of D’Annunzio or Henry Bataille. These movies were vehicles for the new divas, Lyda Borelli, Francesca Bertini, and Lina Cavalieri, and soon eclipsed the spectacular film, imposing melodramatic screenplay and stories about seething passions. This so-called “diva-film,” based on glamorous movie stars, was greatly inspired by modern art and the sensual figures of Liberty. Among the most known movies of the genre we find Thaïs, Satanic Rhapsody, and Carnevalesca.

The plots of these movies were love dramas, turbulent love affairs and stories of death and moral slavery, with performances often prone to redundant excess. Everything in them was extravagant and excessive, but the fundamental value of these films was the creation of a new figure that would have much weight in the history of cinema: the diva, the ideal female fatal, imported from the Scandinavian film (the vamp, woman-vampire). The movie star — the female divas then also male divis — were essentially figures defined by their public image which was enhanced by newspapers, radio, and all possible media in addition to the screen.

The genre reached its peak between 1915 and 1921 and played a crucial role in the discovery of the close up shot and all its infinite expressive possibilities. The shots were often long and fixed, with bodies stretched in aesthetic poses more suited to contemplation than to narrative. In fact, the plots were often implausible and the stories were in fact mere excuses for the long shots of the dream-like divas and divis. This style in Italian cinema set an example for cinema throughout Europe, one more interested in the descriptive and contemplative vision of each shot instead of the speed of the story. The German Expressionist cinema and French Avant-Garde then elevated the close up to its place in the history of cinema.

The star system was already linked to advertising, creating expectations in the public and ensuring high box office results, and was soon exported to the United States where it became the institution we know today. Filmic performers began to specialize in acting styles, from the most natural (based on simplicity and relaxed poses) to the most overloaded and excessive. The best actresses were able to change acting styles from one film to the next, and from one genre to another.

The best representative of the Italian diva of the time was without doubt Eleonora Duse, who gave dignity to the art-film genre in the 1916 film Ceneri, based on the book by Grazia Deledda. She played an old mother, weak and abandoned, full of a human realism. Her talent was rediscovered and understood only much later.

Following the example of Cabiria, other producers started producing films with musical scores written by the great performers of the contemporary music scene. Rhapsody Stanica of 1915 saw Lyda Borelli playing on music written by Pietro Mascagni. In 1916, the diva Lyda Borelli acted in Malombra, based on the novel by Fogazzaro, and launched a new genre, the Gothic style.

After the war Italian cinema could no longer compete with Hollywood and was soon surpassed by American productions in number, but certainly did not fade into obscurity. Through the twentieth century Italy continued to produce films, directors, and actors of great skill and eloquence, as we shall see in the continuing exploration of the Italian silver screen.

By Andrea Nicosia