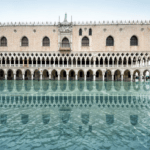

Almost four years have gone since the damage wrought by the 2019 rising tide. Four days of fire for Venetians who experienced the tide surge over the limit of 140 cm four times in a single week: from September 12 to September 17.

Instead, we may breathe a sigh of relief today, because the Ministry of Culture has won a 3.3 million euro appropriation under the “Strategic Plan 2021-2023 – Major Cultural Projects.”

In summary, what happened

The second high-water event in Venice’s history occurred between November 12 and 17, 2019, trailing only the flood of 1966.

High tides have historically been harmful to these lagoon areas, according to the course of time. This is not due to chance or bad luck. In a nutshell, the construction site has begun, but first, let us examine the tragic previous history. We shall accompany the way to a collection of photographs carefully picked to best convey the anguish and tragedy of this event that occurred only four years ago.

Venice Lagoon: an invaluable resource safeguarded for millennia

The first safeguards for the Venice Lagoon and its monuments were put in place around 1930. The damage caused by the phenomenon of high water to the static sealing of lagoon buildings became clear, particularly in the second half of that decade. Beginning in 1937, many rules were enacted to maintain the lagoon by cleaning the canals and combining the houses.

A particularly violent flood swamped the lagoon on November 4, 1966, with the tide reaching 194 cm. The damage was extensive, and things had to alter. This flood is still remembered as the most disastrous, terrifying, and damaging in the history of the Venetian Lagoon.

The first special statute for Venice was passed on April 16, 1973, after a two-year legislative procedure. The topic of city protection was given the distinguished designation of “pre-eminent national interest.” The law specified the goals and conditions for the interventions to be carried out in the lagoon. The story continued with the establishment of numerous lines of defense against the timely action of salt water, ranging from glass panels to the well-known and much-discussed MOSE (traduced: electromechanical experimental module).

This technique appears to be functioning quietly in 2023, even if it is now only in effect at tides surpassing 130 cm (the tide exceeded 140 cm in 2019).

Restoration of St. Mark’s Basilica

The winning company has promised that the restoration work will take no longer than two years and four months. We hope that the deadline will be met in order to conserve the remarkable creative and cultural resources under consideration.

Here is an excerpt from the architect Mario Piana‘s intervention (traduced):

” Every invasion due to the tide, sometimes submerging the base of the building for more than a meter, has meant the action of significant quantities of salt water that have exasperated the degradation of the stones and marbles that cover it. A particularly concerning fact because their thickness, very thin, rarely exceeds 3 cm, but also of the sculptural apparatus, the floors in opus sectile and tessellatum, the same wall mosaics. […] The stone and marble crusts that cover the inner walls of the north wing of the narthex, as well as the opus tessellatum flooring around the Blessed Sacrament, have been particularly damaged by the great invasion of November 2019”.

An eye for the marble narthex, a type of atrium used in early Christian basilicas. The goal of the mineralogical-petrographic analysis is to slow the corrosive impact of salt water as much as feasible.

The entire floor space around the Blessed Sacrament was particularly impacted, with about 2 square meters of surface destroyed during the different floods, as well as bulges spreading across the entire pavement.

To reduce the harm as much as feasible, it is critical in these conditions to nip the corrosive effect of salt in the bud through multiple desalination interventions utilizing distilled water and Japanese paper packs. Obviously, this is not always achievable, and while effective, it is always required to combine restoration work to return structures to their original state.

The project is quite complex. The plan is to remove the flooded flooring and replace it following a waterproofing and salt removal treatment.

Instead, the restorers will work hard to rebuild the mortar patterns while keeping the tones and aesthetic style in mind.

We merely have to wish the insiders well with the restoration of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice. Best wishes!