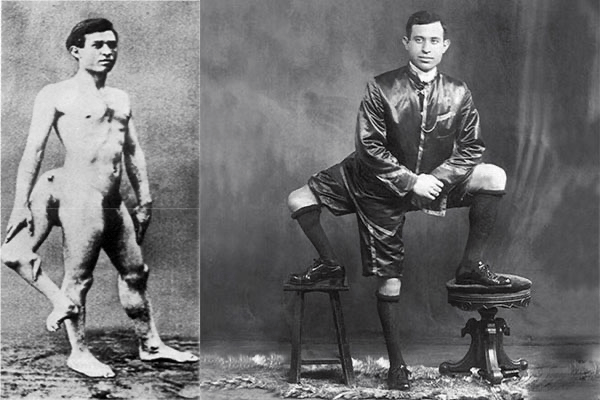

Last month, Italy celebrated an anniversary considered by many a symbol of failure: failure of the power and capabilities of Italian diplomacy, but also failure of the State to care for the well being and safety of its citizens. Massimiliano Latorre and Salvatore Girone have been held captive by Indian authorities on Indian territory since the 15th of February 2012, accused of having unlawfully shot two Indian fishermen dead, while working on the Italian ship Enrica Lexie. The case has barely left the news since, and had been defined by current foreign minister Gentiloni “an open wound” for the country.

Their permanence on Indian soil has now hit the three years’ notch, among new accusations, (failed) diplomatic efforts, illnesses and potential dangers. The Caso Marò (“marò” is an Italian military slang term used in the Navy, that means generically “sailors”), as it is known in Italy, is far from being solved and is widely considered by the Italian public opinion as yet another indelible stain on the image of the Italian Governement and Foreign Affairs Ministry, uncapable to find a solution and to say no to the demands, requests and pretenses of India. Many Italians considers the two Marines innocents, others do not: yet, they all agree the State has failed to accomplish quick results to bring two of its citizens to safety and, if deemed necessary, to start a fair trial.

The case is complex, as it does not only involve International laws and diplomacy, but also because it created a series of questions about the Italian State’s capability to act internationally on behalf of its own people. Economical policies have also been called forward as one of the reasons behind Italy’s weak diplomatic work, a factor that has enraged a large portion of the public opinion.

Let’s try to make the point of the situation and to see why the Caso Marò has been, for the past three years, one of the most shameful issues involving Italy and its political and diplomatic powers. The timeline of the events is long and elaborated, just as its legal connotations are.

Caso Marò: the story

Valentine Jalstine and Ajesh Binki, two Indian fishermen, were killed on the 15th of February 2012 near the Kerala coast. On the same day, the Marina Italiana (the Italian Navy) released a statement regarding a piracy attack on the Italian oil tanker Enrica Lexie: on board, with other 4 members of the National Navy, were Massimiliano Latorre and Salvatore Girone. At that particular time, piracy had become an enormous safety issue in many areas of the world, especially in the Indian Ocean and for that reason it had been decided to provide military protection to ships sailing under Italian flag. As a consequence, there was nothing strange in the presence of 7 marò on the Enrica Lexie.

The day after, the Enrica Lexie docks at the Kochi port, in India, after having been asked by portual authorities to do so in order to help in the recognition of pirates. This soon proves to be false, and only a stratagem to bring the Italian oil tanker and its crew on Indian soil. Once in Kochi, the two Italian marines are accused of having unlawfully killed the fishermen. Latorre and Girone stand by their actions, saying they shot in defense of the Enrica Lexie and her crew, which was under the menance of pirates: in spite of having been asked to identify themselves, the crew of the Indian fishing boat failed to do so in more than one occasion, Italian sources say, and this had eventually brought to use of weapons. The Indian police forces do not believe the Italians and on the 19th of February the two Marò are arrested and placed under surveillance in a police guest house.

Italy intervenes in the person of the Foreign Affairs’ vice-minister Staffan De Mistura, who flies to Kochi immediately: India – Italy says – has no jurisdiction on the events of the Enrica Lexie, because it happened in international waters. The Indians, however, see it differently.

At the end of 2012, the two return temporarily to Italy for the Christmas Holidays and promptly fly back to India on the 4th of January “to honor the promise” made to Indian authorities. In the meanwhile, the Indian central govenrment agrees upon the fact the Kerala region (where Kochi is) has no jurisdiction on the case as the accident took place on international waters. All gets transfered to the capital, New Delhi.

In March 2013 the two are once again allowed to travel to Italy in occasion of the National elections and, during their 4 weeks permit, the Italian Ministry for Foreign Affairs decides not to allow their return to India. A harsh diplomatic case ensues, as Indian authorities, in retaliation to it, strip the Italian ambassador in New Delhi, Daniele Mancini, of his diplomatic himmunity, and threaten to arrest him. To avoid it, the marò are sent back to India.

At the end of the same month, a special Indian tribunal guarantees to Italy and the International community that the death penalty will not be applied in the case.

The rest of 2013 passes, with some openings of the Indian authorities to the demands of Italy, which manages to open its own, parallel investigation into the events. The other 4 Italian Navy members on the Enrica Lexie are questioned by Indian Police in November, but not on Indian soil: Italy vehemently opposed their return to India and local police had to talk to them in a video-conference.

Things get rough again when, on the 8th of February of last year, Latorre and Girone are formally accused by Indian authorities of terrorism. In other words, the Indian police say, the two shot not in defense of the Italian crew, but rather with the intent to carry out a terrorist act against India. Italy and the whole EU rise against the accusation, considered out of place. Although the type of charge can imply application of the death penalty under Indian law, Minister for Internal Affairs, Rainath Singh categorically denies the two Italian citizens are at risk.

In August of the same year, Massimiliano Latorre is hospitalized in New Delhi after having suffered an ischemia and is eventually allowed to return to Italy for a period of four months, in order to receive appropriate care. In December 2014, diplomatic tension arises again between the two countries, after the Indian Supreme Court refused to analyze a series of requests made by the two Italian navy men. Also for this reason, the Italian foreign affairs minister Pinotti has refused to send Latorre back to India at the end of the 4 months health permit of which he availed. Latorre underwent heart surgery in Milan, on the 9th of January, and has not returned to New Delhi, yet. Salvatore Girone, on the other hand, is still in India and lives within the Italian Embassy compound.

A complex case

The danger of piracy

As said, according to the highly contradictory and debated reconstruction of the events, the two Italian Marines would have fired against the Indian fishing boat thinking to be about to be attacked by pirates. An essential point needs to be made here: piracy is today the most dangerous and widespread of all sea crimes, especially in certain areas of the world, the Indian Ocean being one of them. If you read “pirates” and think of Jack Sparrow holding a sabre, think again. Today’s pirates have extremely sofisticated weapons at their disposal, always attack undefended commercial cargo ships and often slaughter their crew to obtain both the boat and its content. Other times, they hold sailors hostage and demand high ransoms to their country of origin, or the shipowner. According to the Heritage Foundation, piracy causes, each year, losses between 13 and 16 million USD.

As well explained by Il Fatto Quotidiano in a 2013 article, published in the wake of the Caso Marò, the crime of piracy is defined in article 101 of the UN Montego Bay Convention as “any illegal act of violence or detention, or any depredation, committed for private ends by the crew or the passengers of a private ship or a private aircraft and directed on the high seas, against another ship of aircraft, or against persons or property on board of such ship or aircraft;” article 101 continues stating that piracy takes place outside statal jurisdiction, that is, on international waters. Because of this, each State can individually decide (of course abiding to international law) how legally act against piracy, if a ship flying the national flag is attacked.

In Italy, the legge 130/2011 allows shipowners to, quite literally, hire Nuclei Militari di Protezione della Marina (Navy Members predisposed to this specific duty) in order to protect their ships and their crew. The Nuclei are armed by the Navy and maintain their duties and rights of military officers and executors on board of the ship they are hired to defend. Basically, they are privately hired, yet (and this is important for the Caso Marò) they remain members of the Italian Navy, hence subordinated to the State, which is also responsible for their activity. However, the Nuclei are not internationally recognized as a proper ramification of the Italian army: basically, they are Marines, they wear the uniform, they have army issued weapons, yet, no other state beside Italy recognize their military function. This is an essential point, because it means that, to the Indian state, Latorre and Girone were not on military active duty when the facts happened.

The laws ruling the case

According to international laws, when incidents involving ship crews happens on the high seas (that is, in international waters) the defendant has to be judged according to the laws and norms in force in the state of which s/he is a citizen: this is the principle (called principle of the flag State) upon which Italy reclaims the right to bring Latorre and Girone home and have them stand trial here. The events took place in international waters, the people involved are Italians, they have to be judged in Italy, by Italian judges, following Italian laws.

Indian authorities, however, maintain the incident actually took place in their own waters, consequently giving India the right to hold the two marò and prosecute them in loco. The problem is that, even if there were a manner to solve this specific issue, there would be more legal problems to face because of a blatant lack of judicial clarity in relation to which laws should be followed for the prosecution: should it be Italy, because of the principle, mentioned above, of the flag State or, considering the victims’ nationality, India to prosecute the two? To be kept in mind is also that the St Antony, the fishing boat involved in the episode, did not fly Indian flag and was not registered with the Indian authorities recording national commercial see vehicles, a possible further issue in case of a legal action.

As of now, the two countries have been trying to solve the question diplomatically, but with little success. As a consequence, the most likely scenario for Latorre and Girone is represented by a double, parallel investigation (and trial) in Italy and India and, in case of a guilty verdict in India, by the possibility to serve the sentence in Italy, where the sentence itself could also be modified in accordance to national laws.

If, on top of all this, one places the diplomatic tension between the two parties involved, it becomes clear how public opinion in Italy has, so far, failed to maintain an united front of opinion upon the Caso Marò.

Italy divided over the Caso Marò

In a fashion typical of Italy, the Caso Marò has divided, as said, the country ‘s public opinion. However, even when disagreeing, Italians find themselves united on one thing: criticism against the government and how it has been handling the issue. Pretty much everyone finds that the country’s official stance is one of weak submissal to the views of another government and, mostly and more worryingly, many feel it has abandoned two of its citizens, grossly failing in one of the foremost and essential duties of a state, that of protecting its own people.

Even when trying to show good will, Italy has done so clumsily, by offering money to the two fishermen’s families in exchange for settling the case outside court, a move which has been by many read as an admission of guilt, in Italy as in India.

Those thinking Latorre and Girone should be brought back to Italy to stand trial have longly criticized the country’s diplomatic weakness and failure to provide protection to Italian nationals and service members; critics tend to view Latorre and Girone as little more than mercenaries, who were not actively protecting the country while the incident happened, because privately hired. Underlining this view is, of course criticism for legge 130/2011 itself.

The many versions of the events, some supported by Italy, others by India, have not been helping, especially because not all of them have factual or legal fundament. At the same time, the ghost of evidence manipulation and misinterpretation lurks over the proceedings, to the point that, about a year ago, doubts were officially risen about the compatibility between the bullets that killed Jalstine and Binky and those supplied to Latorre and Girone.

With such a lack of clarity reigning sovereign, the fact that public opinion is still divided on the case seems natural. It is true that both countries have exposed realistic versions of the fact supported, to a certain extent, by factual evidence. Such evidence, nevertheless, has never been solid enough to tip the scale on one sense or the other considerably.

At this stage, it really seems the main issue is not whether Latorre and Girone have fired those shots or not, or whether they are innocent or guilty: a trial will solve that. The main issue is, rather, that they are able to stand a fair and equal trial, where they will be judged according to proper laws, respectful of human rights and of international standards. This is what has worried balanced, properly thinking Italians since the beginning of the case and which should ultimately worry our leaders, too. In spite of all the –right– criticism brought to the Italian judicial system, seen as slow, not always equilibrated and often too complex, it is a system created within the boundaries of value of human life and respect of the individual and what worries many is the doubt India legal system may not be up to scratch from this point of view.

Far from trying to make easy and unjust racism towards a country that has a millenary culture, it is however something to think about. First of all, India, contrarily to Italy, maintains the death penalty within its jurisdiction, a factor that goes against rulings of the EU, which has “a strong and unequivocal opposition to the death penalty at all times.” Is it right, then, to leave two Italian citizens in the hands of a country which is in breech of a human rights’ regulation of this type, especially when there is not even clear certainty such country has legal jurisdiction in the case?

It is not only a matter of death penalty, but also of human rights more in general. Even though India has been working hard to improve its legislation to make laws more respectful of the individual, there is still plenty to do from a practical point of view, especially in specific fields, including the application of the death penalty. Long established social habits, as well as the extension of the country itself, along with its cultural and social variety, have made the uniform implementation of more just laws hard, to the point India cannot yet be considered an entirely fair place to stand a trial. Should, then, two Italian citizens be judged by this system, especially, as said, when jurisdiction on the events is highly disputed?

India has also acted in breech of international law when, last year, it stripped Italian ambassador Mancini of diplomatic immunity and forbid him to leave the country. This went grossly against the Convention of Vienna on Diplomatic Relations, and has been internationally considered a senseless act of the Indian government.

However, Italy has its own bunch of thorny questions to answer, too.

First of all, why use national military forces to work privately in non-military situations, especially when their position has not been internationally recognized? We saw in an earlier part of this article how the Nuclei Militari di Protezione della Marina have not been officially recognized as military équipes by all states: why did not Italy think of this and created decrees apt to protect the Nuclei members while on duty? Even more pregnantly, should their work for private shipowners be considered “being on duty” at all?

To many, including who is writing, the work of the Nuclei has nothing to do with a military mission: in the end, Latorre and Girone were not working for Italy, or fighting a war bearing the name and the interests of their country on their sleeve. They were employed by a private, protecting his commercial interests. This is not, of course, wrong, just a job as any other, but the difference in between what Girone and Latorre were doing on the Enrica Lexie, and serving your country is enormous. In other words, they may deserve a fair trial in their country, but they were not exactly fighting for Italy when the events took place. As a sign of respect for those who lost their lives while, in fact, fighting for their countries, this should be always remembered.

A right to pay justice to the two victims of the incident stands, in any case, above diplomatic games and international relationships, just as the right of Latorre and Girone to stand trial in accordance to their rights of Italian citizens, as Indian jurisdiction has not been at all clarified. Far from being close to conclusion, the Caso Marò has awakened, as if it were needed, a wave of resentment against the government and the need for official law to deal with the specific case of the Nuclei seems today as essential as ever.

In the meanwhile, Girone remains in India, whereas Latorre is still recuperating from is New Year’s ischemic accident.

A solution for the case appears still distant.