The town of Arezzo, which lies on a low hill of the Poti Alps, opens out fanwise onto the broad, fertile depression in the Apennine mountains, where the upper Arno and Tiber valley, the Casentino, and the Valdichiana meet. The town is the administrative and economic capital of the large province of the same name, and over the last fifty years it has been transformed.

Growth has been rapid, enabling Arezzo to become, amongst other things, a major goldsmiths center. The town’s other vocation as a leading tourist attraction, and its ability to combine a long and great cultural tradition with its modern entrepreneurial identity, make it a major point of reference for the whole of eastern Tuscany.

Down the ages no fewer than eight defense walls, each one larger than the previous system, have encircled the area around the top of the hill on which the ancient town was built: the last walls, built in the 16th century, effectively curbed urban expansion until modern times.

Each time the town pushed its boundaries further and further outward a new Arezzo emerged but succeeded in blending into the town that existed before it. This is indeed the key to historical Arezzo identity: a sum total of very different parts of medieval Arezzo, the town of the grand-dukes, the town under Medici and Lorraine rule. This fundamental aspect of the town’s character, tastes and lifestyles, also helps us to appreciate how a “new” town, inspired by late 19th century principles of town-planning, could so readily bond onto the “old” town.

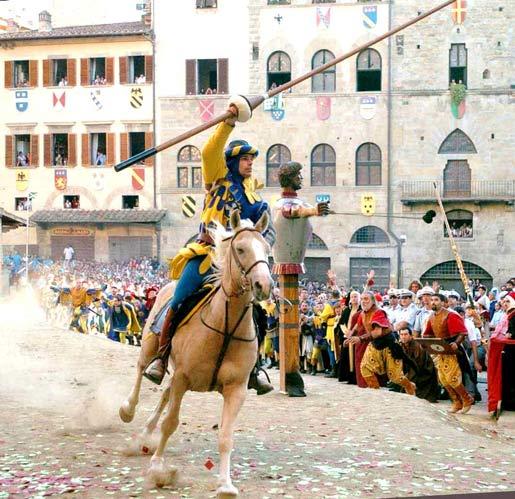

Up at the top of the hill, Piazza Grande is, and always has been, the town’s pulsating heart. The forum of the Roman city was in or near this square.

Like the walled Etruscan settlement before it (6th – 5th century BC), perched between the hills of San Pietro (where the cathedral now stands) and San Donato (today occupied by the Fortress), Arezzo used to be a major center for farming (celebrated for its spelt wheat) and industry, and is indeed believed to have been one of the most important in the ancient word, together with Rome and Capua. It was famed for its bronze statues and terracotta items, and the works that have come down to us (including the bronze Chimera, now in Florence) show the level of technical and aesthetic sophistication the local school had achieved. In Augustan times, items made of “sealed Arezzo earth”, a high-quality ceramic, were much sought-after items.

“Alas! Now is the season of great woe”, sang the great 13th-century poet Guittone d’Arezzo who, after a political career amid the Guelphs of his town, turned to literature as a vehicle of peace. Toward the end of the century, the defeat of Arezzo by the Guelphs of Florence at Campaldino (1289), was a severe blow to the pride of the rich and powerful Ghibelline commune which had adorned its ” acropolis” with churches and public buildings. The walls built in 1194 (the fifth system, along what is now Via Garibaldi) enclosed a town of 20000 inhabitants, organized into the four quarters that compete in Saracen Tournament to this day. The Studio Generale, or university (the successor to the episcopal school whose illustrious pupils included Guido Monaco), added cultural luster: Arezzo yielded such geniuses as Guittone and the eclectic Ristoro. Between the 13th century-medieval Arezzo’s golden age- and the 14th century, the town spread out in a fan-like formation still evident on the town map, with main thoroughfares leading out toward the Chiana river and toward Florence, confirmation of the common interests and destinies of the two cities.

Before Florentine expansion overwhelmed Arezzo’s independence for ever, the town enjoyed one further period of splendor, during the years of the pro-imperial bishop Guido Tarlati (1319-27). With the economic and cultural rebirth Tarlati helped to bring about, art and architecture flourished, and work began on the new walls that were to form the biggest defence system the town had ever seen. When Guido died his brother Pier Saccone was unable to continue the work. In 1384 the town of Arezzo and the surrounding territory were swallowed up by the Florentine state.

The 15th century brought both decline (in the population and in the social life) and economic recovery. All the town’s main architects were of course frome Florence: Bernardo Rossellino, Benedetto and Giuliano da Maiano, Antonio da Sangallo the Elder and his brother Giuliano. But it was an architect of Aretine origin, Piero della Francesca (from Sansepolcro) who created a work that is a fundamental to early Renaissance art: the fresco cicle of the Legend of the True Cross one the apse walls of the church of St. Francis. Florentine gran-duke Cosimo I demolished the towers, churches and all other private buildings that smacked of political autonomy. The town lost its most cherished landmarks (including the old cathedral built by Pionta). In their place appeared new walls (1538) and a star-shaped fortress, the ponderous metaphor of Medici might.

Arezzo began to take on its present form in the second half of the 18th century, but it was not until a century later, with the arrival of the railroad (1866), that urban redevelopment really began in earnest. The “new town” grew up alongside Arezzo’s ancient core, without impinging upon it. The town that greets visitors today is remarkable in the sheer abundance of its art, architecture, culture and local traditions. This rich heritage ranging from awe-inspiring monuments to the lesser but no less fascinating treasures offers a unique insight into a town and the civilization it has spawned down the ages.

By: Paolo Borgogni, Area Turismo – Comune di Arezzo