We often forget about the importance in Italian tradition of the day of San Martino. Door to the winter months, yet still steeped in the colors of the fall, it is a moment of harvest celebration and wine making, but also a coffer filled with ancient popular traditions able to bring us back in time, face to face with our beautiful heritage.

If you happen to come on holiday on the Ligurian Riviera di Ponente – the part of the region gently curving towards France – and are anywhere between Savona and the Italo-French border, you’ll notice the presence of a tiny mountainous island, just a handful of kilometers off the coast of Albenga. It’s the Gallinara: a woody hill rising off the sea, with only a bunch of old buildings on top, virtually invisible from land. Today, the Gallinara island is a natural reserve of undeniable beauty, but this is not the reason I’ve chosen to start this piece talking about it. You see, the Gallinara is a bit of a holy place, too.

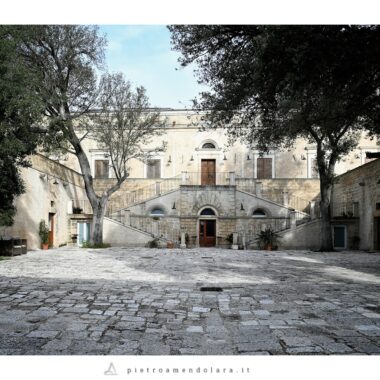

In the early years of the 4th century, a young Martin of Tours (not yet a saint, not yet “of Tours”) sought here quiet and solitude to reflect upon his blossoming spirituality. For a while, he became a hermit and, his biographer Sulpicius Severus tells us, almost died there, poisoned by the wild roots he had chosen as his only sustenance.

Every time I see La Gallinara, I think about Martin and the amazing story of strength and faith of this early symbol of Christian sainthood. This time of the year, I also think about its feast, on the 11th of November, because it’s a pretty important day in Italy. Mind, it’s not a holiday and it’s not necessarily celebrated grandly everywhere, but the day of San Martino repletes with traditional meanings. For those who grew up in the countryside like me, Saint Martin’s day has the sweet scent of young wine and the fragrant, slightly pungent notes of roasted chestnuts and wood burning in the kitchen stove. The ties between fall, its rhythms and the day of San Martino are strong and present a bit everywhere in the country, mirror to our farming tradition and heritage.

A brief history of Martin

Just a few lines to give a face and a story to the name Martin.

The patron saint of France was, in fact, born in modern Hungary, which at the time was called Pannonia and was part of the Roman Empire: the year was 316 (or 336) AD. Martin came from a family of soldiers, as both his grandfather and his father were members of the Roman army: even his name comes from the world of war, as it honors its Roman god, Mars. When the time came, Martin was initiated to a military career, too: he remained a soldier for about 20 years before the event that changed his life took place.

Hagiographical accounts tell us Martin, one night, met an almost naked pauper, trembling for the cold. Immediately, the soldier took his sword, halved his cloak and gave a part of it to the man. Soon after Martin, who had met Christianity while living in Pavia with his family, converted, was baptized and entered monastic life. As a man of Faith, Martin traveled a lot, bringing Christianity in many areas of the Empire, only to stop in France, where he eventually became bishop of Tours. He died on the 8th of November 397 in Candes and was buried in Tours on the 11th of the same month: this is why we celebrate him on such date.

Il giorno di San Martino and its historical background

I mentioned how the feast of San Martino is associated, a bit everywhere in Italy, to the reaping of nature’s bounty and its celebration. But why? According to historian and author Alfredo Cabbiani, the feast of Saint Martin gained relevance also thanks to the moment in the year it fell into, which had been celebrated for centuries by pagans as the end of the Samhain festivities. This habit remained entrenched in European tradition until the 8th century, well into the Christian Middle Ages.

At that time, Martin was already a popular and revered saint in the West, so much so the Church decided to take advantage of the fact the anniversary of his death happened in early November, and used it to transform a largely pagan recurrence into a Christian one. In order to do so, many of the habits and traditions associated to the Samhain celebrations were transferred to the day of San Martino, which became a time of change and new beginnings: change of season, of course, but also the moment where the fruits of the latest harvest start to be enjoyed. New beginnings, because all social and civil activities would start then. This remained unchanged for centuries, proof of it the fact that, in Italy, the 11th of November marked the start of parliamentary activities, of agricultural contracts and even of the school year up to the 19th century. It was even the moment popularly chosen to move home: all great changes traditionally took place on Saint Martin’s day.

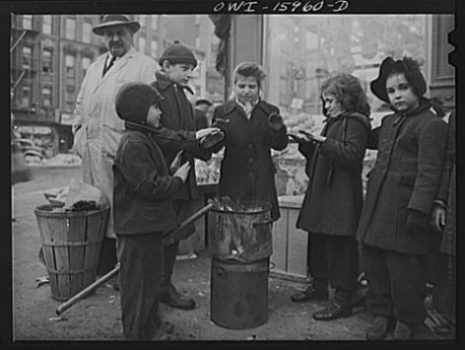

How did we celebrate it? Feasting, of course, just like the old Celts did for Samhain. It was, in the end, the right moment to do so, with new wine almost ready and the early fall harvest filling up barns. It is for this reason that Saint Martin is also considered the saint of abundance.

Words, words, words…

All over Italy, celebrations for San Martino have always been more prominent in the countryside. The new vintage is almost ready in early November, which means barrels need to be fully emptied from last year’s wine to be cleaned for the new. For this reason, an old Emilia-Romagna’s saying maintains that par Sa’Marten u s’imbariega grend e znèn, that is, on Saint Martin day young and old get drunk. All over Italy, we like to say that per San Martino si spilla il botticino, or “we celebrate Saint Martin opening a bottle” and per San Martino cadon le foglie e si spilla il vino, “on San Martin’s day, leaves fall and wine is bottled.” As this is also the period of the year when new wine, or vino novello, is ready, we also like to say that per San Martino ogni mosto è vino, “on Saint Martin’s all must becomes wine.”

There is more than wine to think about, though: as another traditional saying teaches us, San Martino is also the day when we enjoy castagne, oca e vino, chestnuts, geese and wine. We know about wine, and chestnuts, the ultimate fall food in so many areas of Italy, can be considered a given of the period. What about geese though?

Well, the roots of this tradition are once more associated with the figure of Martin of Tours. Good old Martin, his hagiographer tells us, didn’t want to become a bishop; he was a humble man, who’d much rather have preferred live a simpler life of prayer so, upon his election, he fled and hid in the countryside around Tours. It was the noise caused by a group of geese that alerted people of his presence and thus forced him to return to the city and take up his new assignment. According to others, the association between Saint Martin’s day and geese is much more prosaic, as these birds migrate south around mid November, reason for which they are easier to hunt and, as a consequence, more common on our tables.

Il giorno di San Martino, Saint Martin’s day, is truly central to the Italian traditions of the fall. In many a way, it’s a symbol of all that this season brings to our lives and, at the same time, a window upon the winter that is about to come. For those among us who care about heritage and the preservation of our past, Saint Martin’s day is also a moment to remember and embrace them, alas, maybe even with a bit of nostalgia.