It’s been a week, but the outrage around the events that followed the Europa League match between Roma FC and Rotterdam’s Feyenoord is still alive and very much kicking. Nowhere like in Europe has sport been brought to such violent extremes, and no sport like soccer has shown such unfortunate ties with violent echelons of society. Sometimes we Italians tend to believe it’s a national issue, but Dutch supporters’ behavior last week in Rome has demonstrated we’re in front of an international problem, which, in truth, only tangentially touches sports, but rather uses sports as an excuse to perpetrare violence, arrogance or political extremisms.

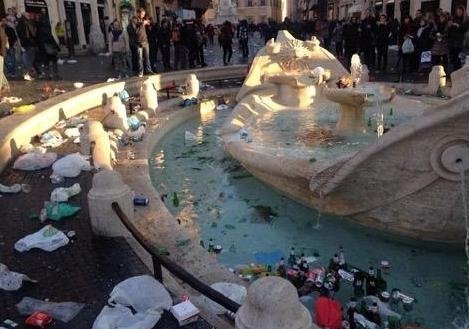

In case you haven’t read about it or heard on the international news, Rotterdam’s own hooligans have created havoc in Rome before and after the international soccer match between Roma and Feyenoord, which took place at the Olimpico last week: ridiculously drunk and shamefully disrespectful of beauty, art and people, a bunch of hooligans took the historical centre of Rome hostage for a whole day and made it their own open air drinking spot, littering, destroying, soiling our beautiful capital, which is by the way a patrimony belonging to every citizen of the world, not only to we Italians, with their urine and excrements.

The most painful of all acts has been the defiling of Bernini’s beautiful fountain in Piazza di Spagna, lovingly known to Romans and Italians all as La Barcaccia, which has been used as a target for beer bottle throwing and penalty kicking competitions among violent drunkards. Riots have been barely contained by Italian Police who, in spite of the arrests, has been bitterly criticized for its work: where did things go wrong and why was this allowed to happen, in spite of the precautions implemented in occasion of the match?

The Events

There’s little to say that hasn’t been said already about what took place on the 19th of February 2015 in Rome. I’ll give you a brief summing up: Roma FC and Feyenoord were due to meet in occasion of a Europa League match. For those not following the soap-opera like events of European football, Europa League is the “second best” European soccer tournament, the first being the Champions League (to which only the first three of each National league take part).

Some fringes of Feyenoord supporters were known to the police for being violent and problematic, hence heightened security measures were implemented in the city, including a strict limitation of alcohol sales. However, something went wrong: apparently, illegal sales of liquor and beer had been taking place at several locations around the city, in spite of both legal restrictions and police controls. Hooligans took the city centre literally hostage, creating problems to many shop and business owners. Many restaurateurs complained about the unspeakable state the Dutch gangs left their premises in. The worst still had to come, though. Fueled by alcohol and supported by their own lack of education, they began using Bernini’s famous Barcaccia as a dumpster for beer bottles and fast food wrapping papers. Once finished with the slaughter, they moved on to the Olimpico where the match took place and the teams scored a draw.

After the match, law enforcement escorted Feyenoord supporters to Fiumicino airport, where an entire terminal had been closed off and controlled by the Polizia, the Carabinieri and the Guardia di Finanza.

Only later in the week, the full extent of the damage caused to the fountain was truly assessed. According to specialists, La Barcaccia, which had been fully restaured last year, has suffered irremediable damage. Hooligans’s behavior has received bitter citicism not only from the Italian government, but also by the Dutch representatives of power, who have strongly taken side against their compatriots’ acts.

The barbarity’s final balance: 28 Feynoord’s supporters arrested, five other mildly hurt. Thirtheen law enforcement members wounded. One unique, unvaluable piece of art violated.

Did something go wrong?

This is what many have thought. The first to receive criticism were the Italian police forces, accused to have underestimated the extent of the Dutch hooligans’s dangerousness. On their part, Police and Carabinieri representatives underlined they acted following pre-organized plans, all the while trying to safe keep residents’ and tourists’ everyday life. The number of agents employed to control the streets of the Italian capital has also been criticized: 1300. Too little for some, too many for others. The first maintaing more forces should have been employed in an attempt to stop violence from flaring. The latter mostly ashamed and incredulous on front of the fact a sport event should need such a high number of policemen to be patroled (as tweeted by @fabriziobocca1).

Italy is not new to soccer related violence: since the dreadful days of the Eysel, in 1986, when several Juventus supporters died during the Coppa dei Campioni’s final between the Turinese team and Liverpool FC (Coppa dei Campioni was the old version of the above mentioned Champions’ League), the country had faced, on an almost daily basis, violence around the soccer pitch: last in time the death of Ciro Esposito, fatally wounded in occasion of the Coppa Italia final between Naples and Fiorentina, which took place last May.

Ultrà, as they are commonly known in Italy, are often politically aligned and associate their purported love for a specific football team with racist and extremist thinking. Antisemitism and neo-fascist ideas are often part of their pseudo-cultural background.

This characteristic is very much common to all European hooligans. Yes, because hooliganism is far from being an Italian-only issue: Feyenoord’s hoolingans responsible for last week events, for instance, are known to international law enforcement for their virulent antisemitism.

Violence and soccer is a relationship that negatively trascends sports and has sociological, cultural, legal and psychological repercussions. There would be a lot to say, yet not enough space to say it. May it suffice to note how incredibly disconcerting is to realize that sport, by concept and ideal a means of unity and equality among men, has become so much intertwined with the hateful crimes of those who nothing know about either.

An International cry against violence and brutality

It is hard to imagine that what happened last week in Rome could have originated something positive, but it has. Of course, both the Italian and the Dutch governments have strongly condemned the acts and have been more or less demagogically trying to decide what to do with those arrested; of course the Dutch Prime Minister has apologized and, of course, Italy is –rightly so– expecting to be refunded for the damage caused to La Barcaccia, a refund that has yet to be confirmed. It’s, however, the words and acts of common people that gives hope: it’s in the online fundrising organized by people in the Netherlands to collect money to go towards the restoration of Bernini’s masterpiece; it’s in the profoundly felt indignation of the people of Rome and of Italy all on front of such barbarisms that gives us a bit of hope that not all is lost.

There is something utterly painful, almost immoral, in disrespecting art and beauty, because through it one shows disrespect to culture and history: when this lacks, it means there is no longer civilization to save and no longer ethical principles to embrace and that, fundamentally, we ignore and disregard our past. Of the danger of such disregard we hear often when talking of the Second World War and its atrocities and how people need to remember in order not to make the same mistakes: there is certainly no need to point out the evident ties between those events and the antisemitic, racially induced violence of so many hooligans groups all over Europe, a frightful sign of how plenty of people do ignore and hasn’t learnt.

But there are also those, and the numbers are not little by the type of outcry risen by the events in Rome, that understand how breaking into pieces a centuries old fountain goes beyond the artistic damage, but is sign of a much deeper malaise, violence, in which plenty still thankfully refuse to take part.

By Francesca Bezzone