If you observe it from a distance as it clings to the edge of the precipice which seems to be attacking it from all sides, the village of Civita di Bagnoregio seems like a ghost town, something that could exist only in the mind of a visionary or in a dream remembered.

Especially on certain misty mornings that little group of houses seems to float surrounded by a fog of unreality. Civita, like an island in our memory or a figment of our imagination, is connected by a single narrow cement walkway to reality and to the surrounding countryside; it is inaccessible to modern means of transportation and takes us far away, not so much in distance as in time.

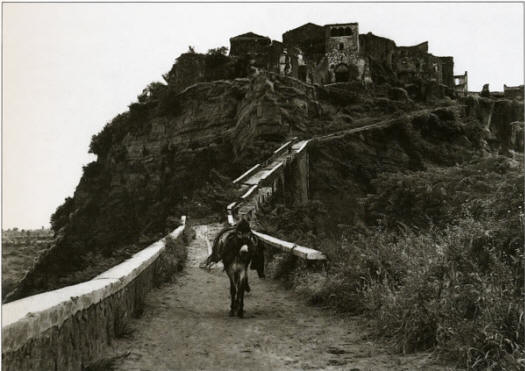

In fact, as one gradually starts to cross this walkway suspended in the air – only 900 feet, but it seems endless – there is a feeling that one is leaving the real world, and this feeling becomes even stronger after entering the ancient city gate of Santa Maria, standing guard over a sheer drop between the remains of two houses with their windows opened wide over the emptiness. One almost has the impression that this gate opens into a supernatural world, surviving in another dimension. And yet, there are plants on the terraces, flowers on the window sills, people moving in the streets, wives and peasants returning from the fields with their donkeys, but it is all in a strangely hushed atmosphere without the noise and stress to which our cities have inured us, in other words it is just as people lived hundreds of years ago. The sensation of emptiness, the void can almost be touched: a street which drops off into the precipice, the facade of a house with nothing behind it.

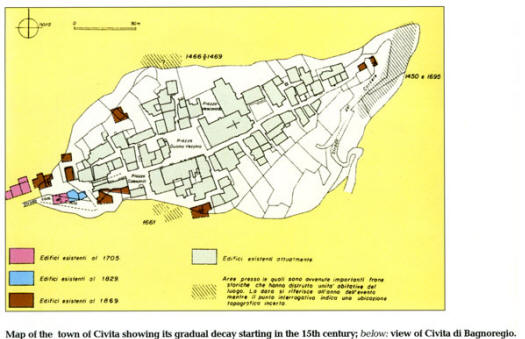

The miracle of Civita is this: a remnant of the past miraculously surviving the passage of time and natural adversities which have changed a rich and prosperous city into a dying town, destined to perish but still clinging to life. This refusal to die is evident in the stubborn persistence of the people who still remain (only about twenty people live in the town all year round; in the Summer the population is about 300), in the meticulous care with which the streets and houses are maintained, and in the enthusiasm for the initiatives which have sprung up for the purpose of giving it new hope to continue to exist.

The most recent of these is the “Civita Project” initiated in 1988 by an association formed of public and private institutions with the intention of creating a research center for the study of new technologies for the conservation and the appreciation of our environmental and cultural heritage. For this reason Civita has become a symbol of the precarious condition in which a great part of Italy’s monuments are now to be found, and hopefully, will also become a kind of ‘mascot’ representing the determination to conserve and renew in order to give a future to our past. Before reaching Civita, the best view of the village is from the terraces of the nearby town of Lubriano, next to the lovely little 18th century church of the Madonna del Poggio, or from the terrace of Bagnoregio.

This village, once just a little suburb of the older and more important town of Civita, is now a lively center for agriculture, commerce and light industry with a population of about 4000; all of the public buildings which once stood on terrain which has been swallowed up in the landslides at Civita were gradually moved here. From these two observation points it is easier to understand the nature of the terrain where Civita was built and the origin of the landslides which, after having caused a major upheaval in the geological layers in the zone, are now laying siege to the last little outpost of houses hovering together in the center of what looks like a lunar landscape or a crater formed by the fall of a gigantic meteorite.

Civita di Bagnoregio is perched on top of a hill at an altitude of 1440 ft. above sea level, between two valleys running in an East-West direction and in which two streams flow: the Rio Chiaro to the North-East and the Rio Torbido to the South. The hill is made up of a layer of tufa (a soft volcanic stone typical of central Italy) about 200 ft. thick which was formed after a series of volcanic eruptions between 700,000 and 125,000 years ago. This layer of solidified lava lies on an unstable base of clay and sand. The numerous shell fossils which have been found in the terrain have made it possible to date the formation to about a million years ago, i.e., to the Lower Pleistocene era.

This was a period of major geological upheaval in which volcanoes sank and lakes arose from the bottom of the sea in the area between the river Tiber and the Tyrrhenian Sea. The clay on the bottom of the valleys is continually eroded by the two impetuous streams and washed away by the torrential rains, leaving bare portions of the tufa bank above, which, without a solid base, soon breaks off and crumbles to the bottom of the valley, leaving new banks of clay exposed along the slopes, and so the whole process of erosion starts over again.

The terrain where Civita stands is therefore particularly unstable and this problem must have become apparent even to the earliest Etruscans, as the many archeological finds would tend to indicate, or perhaps even Villanovan (9th-8th century BC) according to some scholars on the basis of a few artifacts which, however, were both fragmentary and without archeological context. The Etruscans had tried to harness the rainwater and control the flow of the streams by building a system of canals, traces of which are still visible on the cliff where Civita was built.

But in the general confusion which prevailed as the Roman Empire slowly collapsed, the maintenance of the drainage tanks was neglected and the clay became impregnated with water. At the same time, the intense exploitation of the area for agricultural purposes caused the gradual reduction of the number of trees which had always helped to hold the terrain firm with their roots. The erosion of the terrain began in this way and soon reached the city; entire neighborhoods were swallowed up as they dropped off in the landslides, until only the central and most ancient part of the village was left.

While probably repeating parts of early documents which have not come down to us, the first edition of the Statutes of the Commune in 1373 already contained a series of precautions which were to be taken to protect the environment: “Nobody may dig caves in the cliffs around the village of Civita; transgressors will be fined 100 soldi for each offense; nor may anyone dig beneath the city streets…nobody may excavate beneath the locality of the Friars or take their animals to graze beneath the cliffs”.

Text courtesy of Bonechi Edizioni “Il Turismo”