Italy, 1898. Three hundred years after the Triora witch trials, the witches’ screams echoed once again in the quiet, crystal-clear air of the Ligurian mountains.

Someone summoned them. Someone rose them from their sleep of shame and pain, calling them one by one. His name was Michele Rosi and he was to be the first to dedicate a book to the Triora witch trials and their witches: he had decided it was time to talk, to write about them and to begin setting the record straight.

The Triora witch trials and Michele Rosins

This is the story of the women of Triora who, between 1587 and 1589 were imprisoned and lost their lives in name of witchcraft: housewives, healers, midwives, each with something making them dangerous to the well being of the community, or so its leaders would say.

But just as in the Salem witch trials, black magic and conjuring with the Devil had very little to do with the accusations brought to these women: it was a matter of wealth, power and fear.

Thirty three people were accused of witchcraft in Triora, all of them tortured. The destiny of their majority vanished in the spirals of time: etched in the memory of their contemporaries, but lost to records and posterity.

Michele Rosi was the first, after three hundred years of silence, to view up and close the Triora witch trials‘ records, kept in Genoa’s Regional Archives: his work had the merit to rise interest in the events and stimulate further research. Historians’ findings, if possible, make the story of these women even more tragic, as nothing paranormal led to their death: it was human evil to do it, the most real of all devilish manifestations.

Triora, an unlikely setting for a witch hunt

Triora is a quaint little village in the lower Ligurian mountains and there is very little in it, today, frightening or eerie. On the contrary, Triora is well kept, clean and welcoming.

Built on a high point and away from those deep, narrow valleys typical of the area, it gets plenty of sun and light. A bit like Salem, in Massachusetts, Triora has capitalized on its ties with witchcraft, and plenty of black cats, old women on broosticks, moon and stars can be seen on shop signs and porches. Considering the dire destiny of many of the small boroughs of these mountains, which lay empty and dying because of emigration to larger towns and cities, one can really say that, in the end, those 16th century witches saved Triora from a fate of oblivion.

(Luca Galli/flickr)

Burn the witches: here’s how it all started

End of Summer 1587: Triora is a wealthy, strategically located borough with a history of around 1000 years. Its position near the border between France and Italy makes it an important defensive stronghold for the area.

Something, however, is not right: for the previous two years, the harvest has been bad and food is no longer sufficient to feed all of Triora’s inhabitants.

The village leaders, in accord with the Elders’ Council, decide that such a tragedy must be the result of the evil doing of a bunch of local women, all accused of mingling with the devil: witches. These were mostly unfortunate and poor individuals, who survived in the Cabotina area of the village, a grim agglomeration of houses outside Triora’s walls.

A large amount of money was invested in preparing a criminal trial against the first witches and soon the Inquisition, embodied by inquisitors from Genoa and Albenga, the local diocese, arrived in town.

Triora witch trials: when it all gets out of hand

Nobody complained when a bunch of wretched women without a penny were accused of witchcraft, but things quickly changed when the accusations spread like oil and invested the wealthier echelons of Triora’s society.

The Elders’ Council, mostly formed by rich land owners, did not want to see their peers’ wives, mothers and sisters accused of such a deamining crime. Because of this, the trials stopped and, in January 1588, the inquisitors left Triora, but without freeing the women (about 20) still imprisoned.

The village’s authorities realized their witch hunt was getting severely out of hand and decided to take a step back and inform the genoese authorities about it. But it was too late.

Genoa gets involved

Genoa sent over to Triora Giulio Scribani, a former local magistrate, then nominated special commissioner for the case.

Scribani was, in short, a fanatic obsessed with the idea of people relationing with the Devil. Shortly after arriving in Triora, he said “I am here to cleanse this place off that diabolical sect.” And he set out to do just that. Scribani immediately sent to Genoa’s prisons the accused still kept in Triora’s jail and began investigating. Soon, many more were accused, tortured and forced to confess.

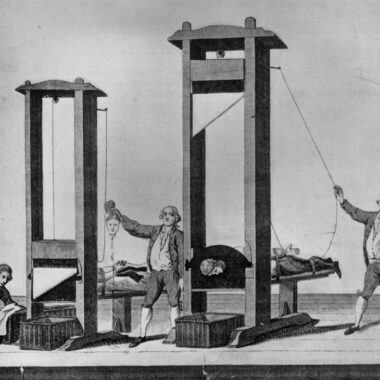

In this, Triora witch trials are not different from others, such as Salem or Loudun: the violence and depravity excercised upon the accused was nothing short of “satanic.”

Scribani’s operate was deemed excessive by the genoese Doge himself, who started to doubt the veracity of Triora’s witchcraft claims: there were simply too many witches for them to be true.

The Doge demanded objectivity and sent over officials to control Scribani’s work. They very much confirmed what was already suspected, but decided to wash their hands of the whole thing, as it was a matter that, strictly speaking, did not compete to the State, but to the Inquisition. Scribani felt, then, entitled to continue his deadly work and many innocent women were accused and executed in those months.

The position of the Church

And the Church? Well, it remained inactive for a long while, but when Scribani showed his true colors, he was excommunicated. The Inquisition eventually decided to close the trials, but four more months passed before this officially happened, during which two women died. Only on the 28th of August 1589 the Triora witch trials reached an official end.

The destiny of the many women still imprisoned remains, to this day, unknown.

What was really behind the Triora witch hunt and trials?

Those of you familiar with the historical interpretations of the Salem events will find many similarities with the case of Triora.

Historians very much agree in saying that, of course, there was no witchcraft behind the accusations, and that the reason used to justify maleficent activities in the village – the caresty – very likely never took place, as all records of the time define Triora as the “breadbasket of the genoese Republic.”

So what happened? It is possible that local landowners wanted to rise wheat and, more generally, food prices to increase their income. Even though the maneuvre aimed at getting more income from their sales to the capital, Genoa, locals paid the consequences more than the genoese, as they became unable to buy food to sustain themselves and their families. Blaming the death of hunger striken people on witchcraft was a perfect way out.

Among the most gruesome and horrendous accusations moved to the Triora’s witches was that of infanticide: however, birth and death records of the time do not show an increase in infants’ death in the area.

More likely was, on the other hand, the presence of expert midwives, with great knowledge of natural remedies, who often “baptized” stillborns or babies about to die in absence of a priest nearby. This practice was common, but not well liked by the Church, and may also be one of the reasons behind the accusations.

Historians have also underlined the possible link between the Triora witch trials and the events, in those very same years, involving Triora’s canon Marco Faraldi, who had been accused of producing fake money and alchemic practices: in order to divert attention from the scandal, Triora’s most powerful may have fabricated the accusations.

Triora today: the witches’ dens

There are plenty of places today where the history of Triora’s witch hunt and trials survives. History – and mystery – buffs may like to take a look at them. Also, you may like to know that Triora hosts, every four years, an international congress on witchcraft and its history.

Lagodégnu

Lagodégnu was defined a “horrid, isolated area” outside the walls of Triora at the time of the trials. Here, the rio Grugnarolo, a small brook, joins the Argentina stream, forming a little lake, considered a perfect witching spot because of the channeling powers of water. Not far from here is the Ciàn der Préve, a field in the vicinity of the medieval bridge of Mauta, also considered a witching area.

The fountain of Campomavùe and the walnut tree wash tub

Water is the leitmotif of all the places once thought to be related to the Triora’s witches: at Campomavùe, people can still find a fountain considered one of their meeting points.

Not far from a walnut tree nearby was a public laundry area with its wash tub, also considered cursed. Walnut trees were commonly known to be loved by witches. Interestingly, the waters of the Campomavùe fountain have terapeutic and diuretic characteristics that, the legends say, were bestowed upon them by the witches themselves.

La Cabotina

This is probably the most famous place in Triora. At the time, the name indicated an area outside the village walls were single mothers, prostitutes and women without a family lived. Marginalized by society, it was easy to point the finger at them when the witch hunt started. Today, the remains of a house are still visitable.

The “Museo Etnografico e della Stregoneria di Triora”

When visiting Triora make sure to check out the museum dedicated to the witch hunt, trials and witchcraft. It is an interesting place, with plenty of historical pieces as well as installations portraying the victims while imprisoned, just as in the witchcraft museum in Salem.

Is there any mystery in Triora?

Well, yes, there is some. For instance, infernal echoes can be found in the name itself of the village, which for some comes from the Latin tria ora, which translates as “three mouths,” just as those of Cerberus, the infernal hound, which is also, by the way, on the village’s coat of arms.

Triora’s main church, the Collegiata, is also said to have a mysterious past, as it may have been constructed on a previous pagan temple. Last, but not least, a fresco of the Last Judgement in the romanic church of San Bernardino portrays dismembered witches, demons and heretics, as well as unbaptized children laying under the bat wings of a demon.

Sounds like the stuff of nightmares.

Read also about Frank Lentini, the 3legged man.

Francesca Bezzone