Major Events in the History of this Art Form

The origins of glassmaking in the area of the Venetian lagoon date very far back in history, with the first reliable reports of activity placing this art form in the 8th century. However, many centuries had to pass before the artisans of the area embarked into what would be the beginning a fully fledged and unique production of decorative glass, evolving over time to reach world-renown fame.

The initial incentive to this production mirrored to a great extent the growth of the Republic of Venice as a trading center and its extensive contacts with territories and cultures bordering on the Mediterranean, where glass making traditions were already well established. Glassmaking practices experienced great evolution following the conquest of Constantinople in 1204 and by the end of the Century, Venetian glassmakers had adapted many of the imported techniques into their own production techniques to obtain unique artistic results.

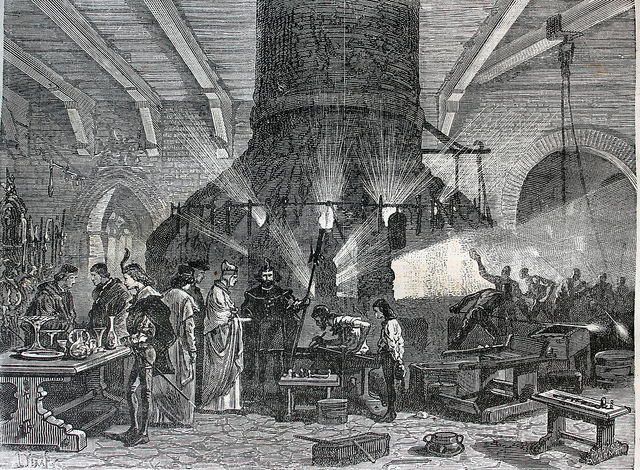

From this period on, glassmaking in the Venetian Republic became one of the traditional and economically significant economic activities. In the 14th century various urban regulations relegated numerous trades to outlying areas in order to reduce risks of fires or disturbance to the population in the crowded areas of Venice. Thus, the furriers were sent to a more remote part of the town, while the glass factories with their furnaces were sent to the outlying island of Murano.

Chronicles of the times report that by the 15th century there were no less than three thousand glass blowers on the small island of Murano. The output of these glass factories continued to be heavily influenced by Eastern traditions, particularly evident in the heavily gilded glassware, or that decorated with enamels. However, in line with the evolution of taste which was sweeping through all art forms, glassware also followed the trend of more elegant and simple styles which became evident in the 16th century. The production of this period is considered one of the most significant art expressions in the history of Venetian glassmaking.

However, by the beginning of the 17th century the period of slow decline in the general political and commercial importance of Venice had initiated. New trade routes emerged that undermined Venice’s trading advantages, and the cultural expressions of the Republic became increasingly ornate.

The baroque tides that overtook all art forms in the 17th century also swept over the glassmaking industry. Very ornate and complex styles were prominent, and the master glassmakers developed new techniques to meet the dictates of the styles of the times. The fame of this refined output was widespread, and specially designed items were commissioned by the courts of Europe. For example in the early 1700s King Frederick IV of Denmark purchased a unique baroque collection that is to date exhibited at the Rosenborg Palace in Copenhagen. However, during the course of the century, new rival glassmaking centers were being established in Europe. Gradually, the major industries in Venice declined, including glassmaking, trade (particularly of spices), shipbuilding, and lace, wool and silk making. Among the glass items which continued in production, however, were beads, luxury beverage glasses, and mirrors.

Austrian Rule and the art of glassmaking in Venice

A further setback in the fortunes of the Republic came with the conquest of Venice by Napoleon in 1797 and the subsequent transfer in 1814 of Venice to the Hapsburg Empire.

The Austrian rule had profoundly negative effects on the glassmaking industry in Murano because the government enacted legislation which restricted the production of glass on the island to favor Bohemia, the other glassmaking area in the empire. Taxation and limited markets resulted in a sharp fall in the number of glass furnaces on the Island. It is reported that from 24 in 1800 they shrank to 13 by 1820. And the production was mostly of decorative beads used for trade, while the production of the artistic blown glass pieces on which the fame of Murano had been established, was largely set aside.

However, in the mid-19th century the tide of decline was reversed. For the first time in many years a new glass furnace was established. The firm called Fratelli Toso was inaugurated in 1854, and this was followed by another firm in 1859 called Salviati. Both firms initiated with utilitarian products, the first to make every-day glassware, the second to produce tiles to repair mosaics. However, the master glassblowers who gradually assembled in these two firms were among the many who had kept the glassblowing traditions alive, maintaining alive the art of the fathers and grandfathers, and rediscovering the ancient glassmaking techniques. Among these was Lorenzo Radi, who had tirelessly studied the sophisticated glassmaking techniques from the 1400s and other special techniques, including chalcedony glass.

The output from the Salviati factory gained international recognition at the London world exhibition in 1862. This recognition of artistic merit was paralleled by commercial success, and the firm soon inaugurated a sales office in London in 1868. These initiatives opened new markets for Venetian glass beyond those in the Hapsburg Empire. Eventually, Venice was freed from the Austrians in 1866 and became part of the Kingdom of Italy. Gradually, the glassmaking industry of Murano began to expand commercially and many new firms were established.

Beyond drawing on the centuries-old traditions of glassmaking in Murano, new influences were inspiring the industry, in particular the reawakening of artistic and intellectual forces in Venice itself. The first Venice Biennale in 1895 brought an influx of new thoughts and art forms from all of Europe. As a result new designs and artistic expressions were adopted by glassmaking that to date continue to evolve. To the present day, Murano producers continue to be at the cutting edge of skill and design for the output of top quality glass of high artistic value.