When, in 1954, Hemingway stood in the baroque haughtiness of Piazza Galimberti, in Cuneo, he was already a famous personality in Italy and everywhere else in the world. His permanence in this algid north western piedmontese city, shaped by the Romans (it has the typical urban structure of a castrum, the ancient Romans’ military camp, where all streets are perpendicular to each other), crowned by the Alps, was only a few hours long, just the time to try out something his editor in Milan, Mondadori, had raved about during their most recent meeting: cuneesi al rhum. A velvety chocolate cream laced with sweet rum, encased in a thin layer of merengue and cover with a shell of fine, dark chocolate, these luxurious, tiny works of art are as known in Piemonte as the Savoias and, no matter about it, they must have bewitched Hemingway, too, if it’s true he bought, on that faithful day of so many years ago, more than four pounds of them.

A little story, sure. Futile, you may say, yet it shows how Hemingway’s relationship with Italy passed also through its gastronomy and the places where food was consumed. Food and its surroundings became constant narrative elements in Hemingway’s prose, with an attention that went beyond ingredients and geography: food became a mirror to places, places became the reason why certain things tasted in a certain way. Let’s take a short, yet enchanting and tasty trip, through the places of Hemingway’s Italy and the words describing his favorite Italian flavors.

Hemingway in Italy

Hemingway‘s first time in Italy wasn’t a happy visit, it was a war. 18 year old Ernest had come to Europe as a soldier and, in 1918, he encountered the charms and beauties of the Eternal Country for the first time. Because of his poor eyesight, he was assigned to support duties and ended up collaborating with the Red Cross as a driver. During one of his missions, he was severely wounded when a mortar shell exploded only a few short steps away from him, leaving him with hundreds of shrapnels wounds.

Hemingway during his wartime permanence in Italy, in 1918 (wikimedia)

Hemingway during his wartime permanence in Italy, in 1918 (wikimedia)Hurt, he nevertheless managed to help an Italian soldier to safety, reason for which he was to be awarded the Italian Silver Medal of Bravery.

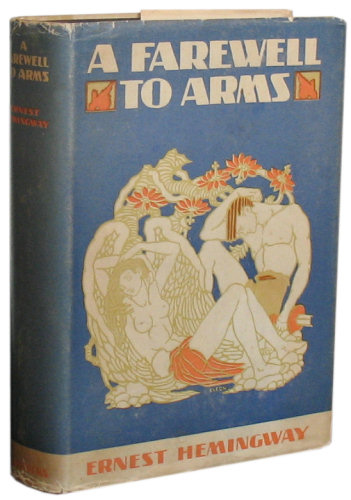

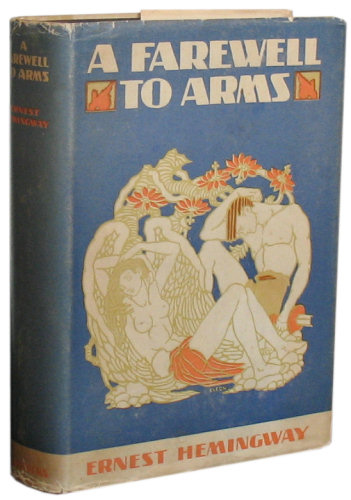

After the accident, Hemingway spent six months in a military hospital in Milan, an experience he was to recount in one of his novels, A Farewell to Arms![]() , written 10 years after the events. These first sketches of Italian life and heritage remained entreched in the writer’s heart, to the point he was to return to the country several times during his turbulent existence. Just as it happens to a besotted lover, the more he spent time beholding the object of his desire, the more his love for it grew and deepened, becoming part of the ethereal essence of his soul.

, written 10 years after the events. These first sketches of Italian life and heritage remained entreched in the writer’s heart, to the point he was to return to the country several times during his turbulent existence. Just as it happens to a besotted lover, the more he spent time beholding the object of his desire, the more his love for it grew and deepened, becoming part of the ethereal essence of his soul.

Hemingway’s Places

Lake Maggiore and Stresa. Two months after the injury that kept him hospitalized for half a year, Hemingway was given a a 10-day convalescence leave. He decided to spend it in Stresa, on the Borromee Islands of Lake Maggiore. Here, he contemplated the beauty of nature – and undoubtedly the inhumanity of war – in suite 106 of the Grand Hotel des Iles Borromées and spent time socializing in its trendy bar over a dry martini, his favorite drink at the time.

His stay in this idyllic part of Italy was eventually narrated in A Farewell to Arms and vestiges of his presence still linger in the Grand Hotel itself, where suite 106 is today known as “Hemingway Suite” and a cocktail named after him can be enjoyed in its bar.

Venice and Harry’s bar. Hemingway visited Venice for the first time in 1948. During this first visit, he wrote another of his masterpieces, Across the River and Into the Trees![]() , entirely composed while staying on quaint Torcello. It was, however, at a later date the writer engaged with the city more actively: here he decided to spend some time in the mid-50s, after himself and his fourth wife had been victims of a frightful plane crash in Uganda. It’s during this period that Hemingway became an habitué at Venice now ubiquitously famous Harry’s Bar. Giuseppe Cipriani, its founder, well remembers Hemingway’s visits to the establishement and the liking he took to a specific corner table he was to mention in Across the River and Into the Trees.

, entirely composed while staying on quaint Torcello. It was, however, at a later date the writer engaged with the city more actively: here he decided to spend some time in the mid-50s, after himself and his fourth wife had been victims of a frightful plane crash in Uganda. It’s during this period that Hemingway became an habitué at Venice now ubiquitously famous Harry’s Bar. Giuseppe Cipriani, its founder, well remembers Hemingway’s visits to the establishement and the liking he took to a specific corner table he was to mention in Across the River and Into the Trees.

Hemingway became a fan of Harry’s Bar “Montgomery,” a dry cocktail made of 15 parts gin and 1 part vermouth.

The Grand Hotel des Iles Borromées where Hemingway spent time after being injured in a war accident

The Grand Hotel des Iles Borromées where Hemingway spent time after being injured in a war accident(Dennis Jarvis/Flickr)

Italy and its food in Hemingway’s words

On a dinner in Milan and a late walk under the Galleria:

(…) Afterward when I could get around on crutches we went to dinner at Biffi’s or the Gran Italia and sat at the tables outside on the floor of the galleria. The waiters came in and out and there were people going by and candles with shades on the tablecloths and after we decided that we liked the Gran Italia best, George, the headwaiter, served us at a table. He was a fine waiter and we let him order the meal while we looked at the people and the great galleries in the dusk, and each other. We drank dry white Capri iced in a bucket, although we tried many of the other wines, fresa, barbera and the sweet white wines (…).

After dinner we walked through the galleria, past the other restaurants and the shops with their steel shutters down, and stopped at the little place where they sold sandwiches; ham and lettuce sandwiches and anchovy sandwiches made of very tiny brown glazed rolls and only as long as your finger. They were to eat in the night when you were hungry.A Farewell to Arms

A Farewell to Arm’s First Edition (wikimedia)

A Farewell to Arm’s First Edition (wikimedia)

On mortadella, its flavor and the loving – if somehow gritty – care taken by Italian women in slicing it:

Then he said to the woman in the booth, “Let me try a little of that sausage, please. Only a sliver.”

She cut a thin, paper thin, slice for him, ferociously, and lovingly, and when the Colonel tasted it, there was the half smokey, black pepper-corned, true flavor of the meat from the hogs that ate acorns in the mountains.

Across the River and Into the Mountains

On a fishmarket in Veneto:

In the market, spread on the slippery stone floor, or in their baskets, or their rope-handles boxes, were the heavy, gray-green lobsters with their magnets overtones that presaged their death in boiling water. They have all been captured by treachery…and their claws are pegged. ……There were medium sized shrimp, gray and opalescent, awaiting their turn, too, for the boiling water and their immortality, to have their shucked carcasses float out easily on an ebb tide on the Grand Canal. The speedy shrimp, with tentacles longer than the mustaches of that old Japanese admiral, comes here now to die for our benefit. Oh Christian shrimp…..master of retreat, and with your wonderful intelligence service in those two light whips, why did they not teach you about nets and that lights are dangerous?

Across the River and Into the Mountains