…There is more to Italian cuisine than pizza and pasta… As we know, there’s also a category of weird Italian food that we must discuss now.

If you are an attentive reader of ours and a food connoisseur, you know already there is more to Italian cuisine than pizza and pasta. What you may not know is that some of our most traditional dishes have peculiar ingredients indeed: from chicken giblets to offal, from chitterlings to snails, we Italians truly cook everything.

For some Italian recipes, you may not be brave enough to try

Weird Italian food to many, but a true symbol of a culinary tradition that has dealt, throughout the centuries, with poverty and famine with a certain “aplomb,” at least in the kitchen.

Never the one to step back from or refuse a challenge, the Italian cook has always known that everything can be transformed into something nice to eat if prepared in the right way and with the right ingredients: we would say, in Italy, that one needs to fare di necessità virtù, to make of necessity a virtue.

The weird Italian food you will read about in the next few paragraphs were, more often than not, born of necessity: necessity to eat and the necessity to do it without spending too much money, either by using what was more readily available, maybe from one’s own orchard or cheaper to buy.

These weird dishes come from ancient ricette, recipes, typical of certain areas of the country and are traditionally considered piatti poveri, literally, poor dishes, because made with cheap cuts and ingredients. Throughout the decades, however, they started to be so appreciated they became a true culinary must and entered the Olympus of many an Italian ricettario.

Many piatti poveri have a common history and heritage, as well as their choice of ingredients, which usually includes discarded parts of pig and veal, as well as wild animals such as lumache (snails) and rane (frogs), which had already become delicatessen deign of a king in centuries past. Others have acquired a status of cult food in more recent years, also thanks to the rediscovery of traditional Italian cuisine promoted by associations such as Slow Food.

Let’s start this truly peculiar trip through a lesser known culinary Italy from the strange dishes of our beautiful South.

Weird Italian food of the South

Campania: ‘O pere e ‘o musso

The foot and the snout (this is the translation of the dialectal ‘o pere e ‘o musso) is a traditional piatto povero of Campania, where it is often sold as street food, dressed in salt, lemon, and other ingredients like olives, fennel, paprika and lupin beans. ‘O pere e ‘o musso holds a P.A.T. designation, which means it is an officially recognized traditional agro-culinary produce of Italy. It derives, as the majority of the dishes you will come across in this article, from the old-time necessity not to waste food and feed one’s family on the cheap.

This truly strange dish’s main ingredients, as its very name says, are pig’s feet and veal’s snouts, boiled, cooled, chopped into small pieces, and served dressed as we said above. Very often, more offal, such as cow stomachs, is added to them.

Is it good? I do not know, I have never tried it, but it has been around for such a long time it must be, right?!

Basilicata, Calabria (but also the whole North): sanguinaccio

Be careful when it comes to sanguinaccio, because the same name defines two very different dishes, one sweet and one savory, both of them made with pig’s blood (hence its presence in our list of weird Italian food!).

Sanguinaccio dolce (the sweet one) has a P.A.T. designation and is particularly popular in Basilicata, even though it is commonly found in other southern regions, as well as Liguria. It is a custard-like dessert made with dark chocolate and pig’s blood, consumed with traditional bugie or savoiardi, or used as a spread.

Sanguinaccio insaccato (the savory one) is popular a bit everywhere in Italy, from North to South. Even though its composition (and dialectal name) varies slightly from region to region, sanguinaccio always has pig’s blood as its main ingredient. A popular addition to it are spices, milk (in Liguria), potatoes, and bread (in Piemonte).

Savory sanguinaccio has culinary cousins in every corner of Europe: well known is the Anglo-Irish black pudding, but also the German blutwurst, the Spanish morcilla, and the Portuguese morcela.

Little family digression: I am very fond of the savory version of sanguinaccio. My grandmother would buy it every Tuesday and prepare it for lunch when I was a child. It was a huge favorite of my grandfather’s, who grew up in a farm and was a lover of rustic, traditional dishes.

She would usually boil it and serve it sliced, even though, sometimes, she would fry it with red wine and onions and create a sort of velvety sanguinaccio “stew”. For all my childhood I had known sanguinaccio as “bröd”, its name in the Piemontese spoken in my area, and still today I find it hard to call it with its Italian name. Savory sanguinaccio I truly love. Never mind the blood, it is absolutely delicious: think of Irish black pudding, but more delicate in taste and with a velvety, almost creamy texture. Ah yes, I am a fan of this certainly strange Italian dish.

Sicilia: Pani ca meusa

I was in Sicily two weeks ago with my brother and he brought me to see Palermo with a couple of friends of his (one of them was an art historian, who gave me the most amazing private tour of the city). When lunchtime came, the three of them immediately said “we’re going to the Focacceria di San Francesco for a Panino con la milza”. Now, panino con la milza (the translation in Italian of pani ca meusa, which is a sandwich made with chopped veal spleen) is a culinary institution in beautiful Palermo. And when it comes to it, Focacceria di San Francesco is apparently the place to go for it, so I got the best on my first try. (By the way, the Focacceria San Francesco has become so famous all over Italy that it opened also in Rome and Milan).

Having grown up in rural Piemonte, I am used to strange food like that: I told you about sanguinaccio already, and you will see I am on friendly terms with other very strange dishes… So it came as no surprise to me to find the pani ca meusa delicious. The spleen – and sometimes the lungs – of the veal is boiled, then sliced and fried in lard. It is served hot in a small, round bread loaf flavored with sesame, called vastedda. If you want your vastedda only with milza, then you will have a pani ca meusa “schiettu” (simple); if, on the other hand, you want to go the whole nine yards and get also ricotta and grated caciocavallo in it, you will have a pani ca meusa “maritatu” (“married” with the other ingredients).

Pani ca meusa is not a light sandwich, so do not get it as a snack: this is a full meal between two slices of bread, especially if you go for the maritatu (as I did). The combination between the rich flavor of the milza and the creamy consistency of the ricotta gets a nice punch from the salty tanginess of caciocavallo, which balances the sandwich gracefully. To give an idea, milza tastes a bit like veal liver, but it is more delicate: if you are into this type of flavor, you should definitely give it a go.

Weird Italian food of the Centre

Toscana: lampredotto

Lampredotto is a typical (and strange) dish from Florence, made with cow’s stomach, the reason for it becomes part of our list of Italy’s weird Italian food. Just as other dishes mentioned in this list, it is P.A.T. certified. Lampredotto gets its name from its main ingredient, the abomasum, one of cows’ four stomachs, commonly known in Tuscan dialect as lampredotto. It is cooked in tomato, onion, parsley, and celery, then either sliced and served on a plate with a parsley and olive oil sauce or in a local type of bread called semelle. Usually, the top half of the bun is soaked in the cooking juices of the lampredotto, as you do in the US for roast beef sandwiches (which, by the way, I miss terribly: so delicious!). It can also be served as a stew with chards, a concoction known as lampredotto in zimino.

Lazio and Tuscany (but also Veneto, Lombardia, Piemonte, Liguria and most of central Italy): la trippa

Trippa (tripes) is the generic name we give in Italy to cow’s stomachs. Plural of course, as they have four. Once again, trippa is a P.A.T. dish and yours truly has grown up eating it. Trippa, both in soup with tomatoes and beans, or as a stew with vegetables, was a staple dish on my family’s kitchen table. My grandma used to make it almost every week. I used to love it served with lashing of grated parmesan and I still do, even though I do not eat it as often now. Among all weird Italian dishes out there, trippa is one of the most ubiquitous and consumed, to the point you can even find it canned, on your supermarket shelves. However, with cuts such as these, quality is essential, so I would refrain from trying anything pre-packed, and would rather choose it from the counter of a top-notch butcher of your knowledge.

Trippa has relatively long times of prepping, as it needs to be washed several times before being cooked – even though butchers today tend to do it for you more often than not – and it needs many hours of cooking.

Among the most common recipes are those of trippa alla romana, made with tomato sauce; Lombardia’s busecca, with tomatoes and beans, served as a soup (like the one I used to eat as a child) and the trippa alla fiorentina, that is, a trippa stew.

Sardegna: casu marzu

Casu marzu is the eythome of weird Italian dishes). It is Sardinian for “rotten cheese,” and that is exactly what you get when asking for it: a full form of pecorino sardo colonized by the larvae of the piophila casei, the cheese fly. The larvae are usually eaten along with the cheese, which gets a soft, at times creamy consistency and a pungent fragrance and taste. The case of casu marzu (pardon the word game) is famous in Europe because official EU hygiene regulations forbid its large-scale production and its sale, even though, of course, you are more than free to buy pecorino and let it rot for yourself to eat. I should not be so harsh towards casu marzu, though: truth is it is a type of food with a long history of tradition, which has rightly gained a P.A.T. denomination. This means casu marzu is a Sardinian patrimony and can – and should – be protected.

Because of its immense importance from a cultural point of view, the Regione Sardegna has endorsed research on how to produce it more safely and has given to the Università di Sassari the duty to grow cheese flies in vitro, so that the whole production chain of casu marzu can take place under full scientific control.

The idea of consuming rotten cheese, sometimes with live beings in it, is not exclusive to Sardegna: variations on the same theme are available in Liguria, Piemonte, Lombardia, France, and Germany.

The Piedmontese version is called brûss and is, along with frog legs, one thing I always refused to eat. The original-recipe brûss, just as casu marzu, is no longer sold in shops, even though cheesemongers do produce a larvae-free, more delicate version of it for commercialization. It is, however, still produced by farmers.

Weird Italian food of the North

Piemonte: cosce di rana

Frog legs: this is what cosce di rana means. These are very popular in France, but also in Piemonte, a region that notoriously has a lot in common with Italy’s first cousin across the Alps. They are extremely common in basso Piemonte, where I come from (the Cuneo province, close to the French border), but also in the area of Vercelli and Novara, where the presence of rice pads has created the perfect habitat for them. For the same reason, they became a common food in Lombardia and Veneto as well.

They are usually battered and deep-fried, although plenty of recipes are available, always involving some sort of frying. Frog legs are a quintessential weird food: why on earth people would decide to eat them defies the knowledge of many, but a lot has certainly to do with the fact rane (frogs) have always been readily available and cheap to get, also in times of war or famine.

Among all frog’s species, only two are edible: the green frog (rana esculenta) and the common frog (rana temporaria). Both of them, however, are protected under EU law, so forget about getting a couple of them next time you come down to Italy and end up near a pond: the number of frogs available for commerce and hunting is strictly regulated. You can find frogs quite easily though, at least in Piemonte, at the fishmongers.

Those who ate them say they taste very much like chicken, but to be honest I have never had the courage to try them, maybe because I do not particularly like the look of frogs when they are alive, let alone dead. If you ever decide to give it a go, they are pretty common in many restaurants and it should not be hard to find them.

Let us know what you think!

Piemonte, Veneto and Northern Italy in general: lumache

Lumache (snails) are easy to find all over Italy and appear on the table in many regions, especially in the North. A dish can barely get stranger than this.

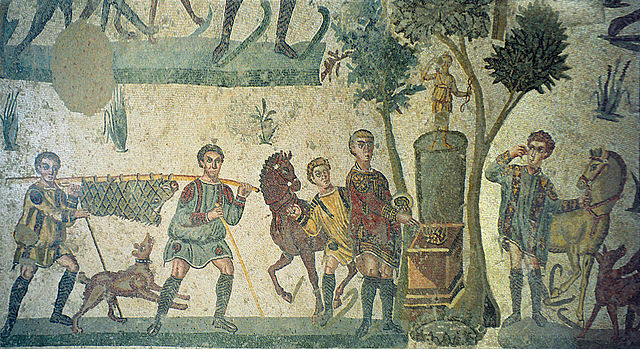

The history of lumache as a culinary ingredient is long and prestigious, even Pliny the Younger in the Naturalis Historia and Apicius in De Re Coquinaria suggested their consumption as food, and provided recipes to cook them. They are also a typical dish of France and Spain (who does not know about French escargots?) In many areas, lumache are bred specifically for sale and human consumption, but more often than not people in the countryside used to pick them in the woods and cook them. This is the memory I have, as well: lumache, just as wild mushrooms, were never bought in my house, they were “picked” during the right season and used straight away, usually cooked “in umido,” that is, as a stew with loads of parsley and sometimes tomatoes and red wine. This is often called ragù di lumache. However, snail picking is today forbidden by law in Italy, in order to safeguard nature. Also, for this reason, snail farming became more common than it used to be.

They have a delicate, yet characteristic taste, emphasized by the herbs one chooses to cook them in. Their texture is, probably, what bothers people the most: they tend to be a bit chewy. Personally, I am not a huge fan, but I do enjoy them every now and then as they remind me of the times and scents of my childhood.

Their “season” in the Fall, a bit like it happens for mushrooms, so if you want to try them in a restaurant, you are more likely to find them in this period of the year.

A weird Italian dish that’s not so weird anymore…

Some of the dishes considered weird a while back are no longer seen as such, as they became increasingly popular, even among the least adventurous of tourists. Almost nobody finds chicken livers and giblets (fegatini) that strange anymore, especially in Tuscany, where they are usually fried in olive oil and eaten layered upon thick slices of deliciously rustic bread. Once again, my rural upbringing comes in handy for an anecdote… My grandfather used to have chickens and he would usually ready one for my grandmother to prepare for special occasions; she would not only keep the chicken’s giblets, but also its comb and wattles, all of which were cooked for me, the youngest of the family, as a treat.

The same can be said for a quintessential Roman dish, la coda alla vaccinara, an oxtail stew flavored with vegetables, most notably celery (1.5 kg of celery for each kg of oxtail). The name of the dish comes from the habit, once upon a time, to pay a cattle butcher (the “vaccinaro”) with parts of the cattle itself, including the tail. The recipe is characterized, besides large amounts of celery, by the addition of cinnamon, nutmeg, and raisins.

As you can see, there is really more than pizza and pasta to Italian cuisine. These dishes are strange indeed, and may not be everyone’s cup of tea, I must admit it, but you should give it a go, if you have the chance, the next time you visit the country. Not only some of them are absolutely delicious, but they are also staples of our cuisine, mirror to our very history. Be adventurous: you may be pleasantly surprised.

Francesca Bezzone

pigs feet the best so good pickled in a gel or in red sauce

oxtails another great dish and the price in the grocery store you can buy steak on sale cheaper lol

Sorry but I do not understand. Sandwich has the same meaning in Italian and English: Meat or whatever between two slices of bread…. So you will have to be more specific than that. In Italy we also have panini wich is basically the same thing. just made with fresh made bread instead of sliced bread.

Agreed 100% We will have to add Rigatoni alla Pajata to the article. Thanks for pointing that out

Where can I find that sandwich now. I haven’t had that in years. My father used to buy them at a store on 2 nd Ave in Manhattan. If anyone knows where I can find them now, I’d appreciate it.

Please my parents are siciliano, and eat on a pretty regular basis lambs heat broiled , tripe and the vastedda are nothing and I hate to say are crazy good , my mom put it under the broiler and the cheese gets nice and hot , delicious .

Growing up in Brooklyn NY blocks from the pier’s where my grandfather & our Sicilian family came to kive & work, they brought with them many “recipes” my grandfather was a butcher in our family store. I grew up eating sweet breads, pigs skin, pigs feet, tripe, vasseda, octopus, snails from the ocean and the mountains. Today people don’t make or eat these foods anymore. I keep tradition and make all of them. Growing up Sicilian was a joy when it came to foods from Sicily.

What a great overview of off-the-wall foods from across Italy! Coming from a very conservative Australian upbringing, some Italian food is left-field but we’ve loved exploring it and testing it for ourselves. Have to say that Lamprodotto was a real surprise, and a good one!