Venetian plaster, or Venetian stucco, has been used for centuries around the world. Time to find out more this art form.

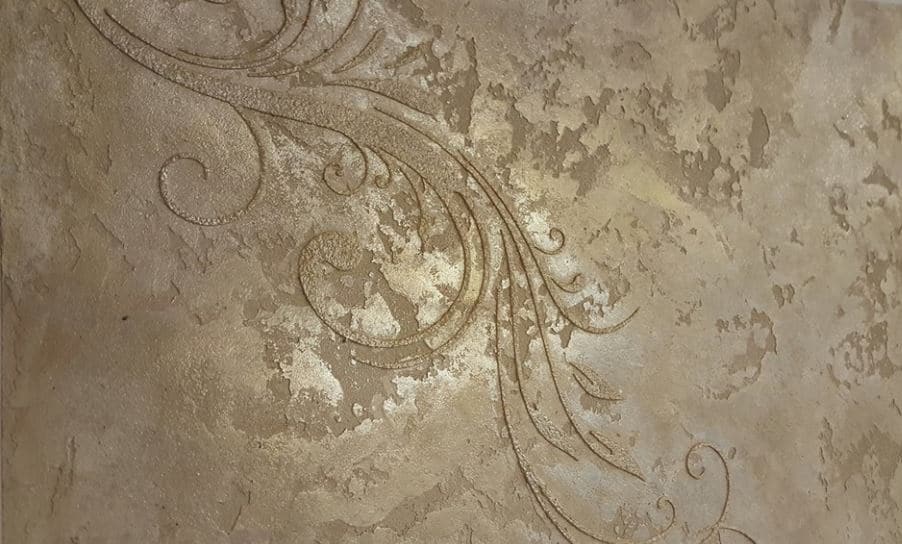

Venetian plaster is distinctive, subtly graduated in color, and can have a rough finish. Although traditionally it is shiny and with multiple layers.

Venetian Plaster History

The origins of Venetian plaster are relatively hidden in the past. Some sources claim all to way to 9000 years ago in Mesopotamia. Other countries and other ages used similar and more and more developed plastering techniques. For example, tombs in Egypt were covered with a lime and gypsum plaster. While entire cities in India were plastered and China used plaster to cover rough stone walls.

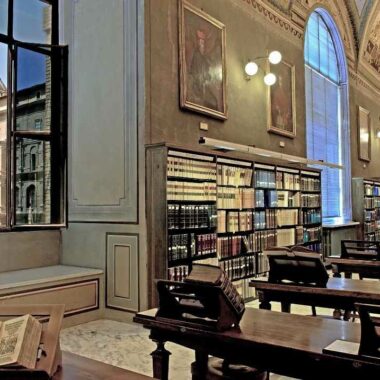

The list goes on and on. Until it reaches Italy. Specifically, Pompeii. Unlike frescoes, Venetian plaster has a smooth surface. Also, it doesn’t feature images or bright colors. In fact, the basic ingredients and processes have remained essentially the same since the first century AD. Artists and architects in the Renaissance embraced it as both an old and new technique. That’s when Venetian plaster became fashionable, for both the exterior and the interior design.

Significant changes in the processes and materials didn’t occur until the mid 1900s thanks to Carlo Scarpa. He was an Italian architect who began using glues and acrylic resins. He also changed the process by taking it from seven layers to three.

The Materials

Creating a finish of Venetian plaster is a complex process. It also features different materials, like limestone, gypsum, malt, beer, eggs, animal hair, and sand. More recently, acrylics and fiberglass. Essentially the base has stayed the same but the specifics have varied. The differences depend on geography, culture, and innovation.

The beginning

In the 4th century BC, the Romans discovered the use of limestone. When they mixed it with silica, alumina or other volcanic material, limestone set and hardened. The Romans kept limestone in pits and dark cellars for three years to allow it to mature. Later, they realized that exposing it to the atmosphere allowed it to absorb atmospheric gases. This neutralized its caustic nature, making it easier to use.

Around the world, plaster wasn’t yet what we know today as Venetian plaster.

A new finish was developed in the fifteenth century. It resembled marble but it was lighter. It was the Marmorino, used for the surfaces of Venetian buildings. Revived in the sixteenth century by Palladio, Marmorino was used extensively in the Veneto region of Italy.

And all of these changes have gone hand in hand with the changes in the actual application process.

The Process

Vitruvius, a first century BC Roman engineer and architect, described a seven-step process. Regardless of materials or number of layers, each layer was smoothed on using varying techniques. And then left to dry. The wall was then sanded and another layer added; a third and possibly fourth (fifth, sixth and seventh) layer, each sanded in turn. And the final layer.F

This sheen is what gives Venetian plaster its fame, and is the result most sought after by those seeking to create an old-world look in their homes or other spaces.

Venetian Plaster Today

Many companies today offer Venetian plaster finishes for your walls. They can be found rampant on the Internet, and all boast of the natural look and feel of their products, especially those who use artificial materials and shortened processes.

The debate rages between purists and those who espouse using today’s innovations. As a result, it is impossible to talk about a typical contemporary process, or typical materials in use. The only consistency is that all good artisans can create a work of art – a surface that is as deep and luminescent as a pearl, offering views of both the world in which we live, and the world of the ancient past.

Visit Italian Frescoes for more pictures of the paintings and procedures.

By Teresa Cutler