In History of Italian Cuisine I, we have begun a tale of food, wars, invasions, and great men that brought us from the dawn of Roman civilization to the very beginning of the Renaissance. We saw how influences from the Germanic people who conquered areas of the peninsula, but especially those from the Arabs of Sicily, helped to create some of Italy’s best-known dishes: marzipan, cassata, even gelato have roots in Arabic culinary tradition. This time, we’ll pay more attention to the Middle Ages, and the Italian Renaissance cuisine.

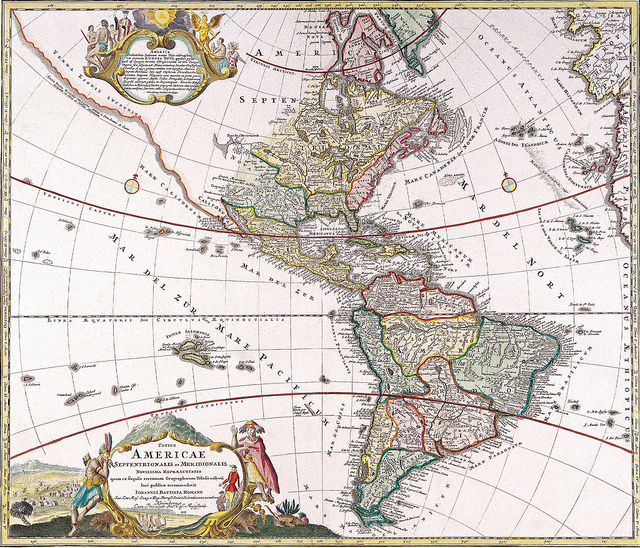

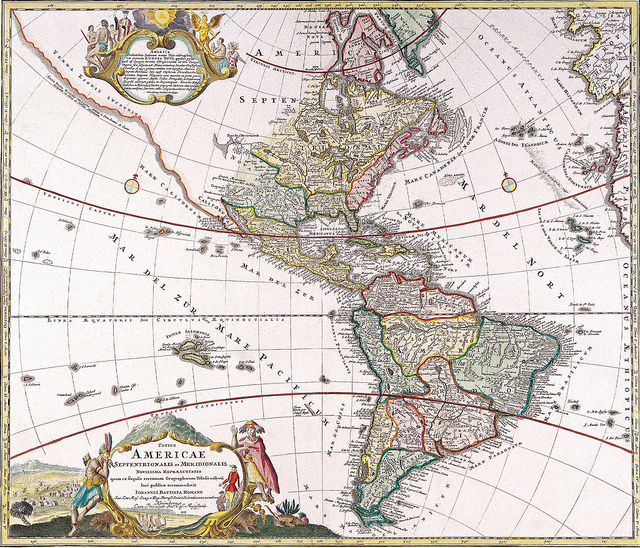

In this section, we’ll take a closer look at the Renaissance courts of the most beautiful cities of Italy, at what was popular on their tables, and why. We’ll also find out the discovery of America truly changed the shape of things in Italy, also when it comes to food: our best ally in the kitchen, the tomato, entered our homes in the 16th century, after Cortèz brought some seeds back from the Americas and drastically modified the way we eat. Let’s see some details about the Middle Ages and Italian Renaissance cuisine.

The Later Middle Ages and the Renaissance in Tuscany

Just as in art and literature, Tuscany was to have an essential role for the birth, or better, the renaissance of modern Italian cuisine. This happened especially in the 14th century when all major signorie in the region began to look with a renewed interest to gastronomical experimentation: it was once again the newly formed commerce, craftmanship, and banking-based high bourgeoisie to call for such a change because food and its refinement was seen as symbolic of their own achieved social and cultural status. Little accepted, when not scorned, by old and traditional noble families, it was also through their culinary knowledge and refined tastes that Italy’s medieval nouveaux riches tried to make themselves respected.

Tuscany was the perfect location to experiment in the kitchen, because all type of produce was available in situ, just as it still is today. Matilde of Canossa first, the comuni and signorie after, had strongly recommended and supported the terracing of great part of Tuscany’s incredibly fertile hills and had taken control of the region’s water supplies. The hills of Siena and Florence became known for their olive oil, peas, and cabbage of the highest quality were produced in great quantity in Scandicci and Lastra a Signa, near Florence. Lambs came from the Casentino area and bovines from the Val di Chiana: the famous Chianina breed of calves is still one of the best in the country today. Mullets came aplenty from the Tyrrhenian coast and pikes from the Chiusi lake. Everything was available in Florence’s Mercato Vecchio, where also plenty of local sellers would converge to propose their own farm products such as milk, eggs, and cheeses. The Chianti area was already known for its red wine, just as were Montepulciano and Montalcino. The Isola d’Elba produced a popular Aleatico, too.

The bread made in Prato was particularly sought after: sweetened with honey and flavored with spices, dried figs, and sultanas, it was the ancestor of Siena’s panforte and Milan’s panettone, both typical Christmas time cakes. Almond confetti was popular in Tuscany, too, where they were used only for special occasions because of their production costs. The wine was consumed in large quantities, also as an antidote and as a narcotic: in a period of devastating epidemics, a glass of wine, often, was seen more as a medicine than a vice.

Italian Renaissance cuisine

When we speak about Tuscany in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, in any case, it is to one city and one family most of us think Florence and the Medicis. The family did not only bring Florence to the apex of the cultural and artistic world and made it an example of beauty and perfection to the entirety of Europe but also set the pace in the kitchen.

Fond of understated luxury, the Medici family never overdid it, but rather demanded of its cooks quality and purity of taste: traditional Tuscan recipes, often inspired by popular flavors and dishes, were served in season, during banquets of the uttermost class, where cleanliness and manners were paramount. Far from the excesses shown by the Romans 1000 years earlier, the Medicis loved simple, wholesome recipes, often centered on the game and home-crafted cheeses: let’s say they were ante-litteram estimators of today’s cucina povera and local produce trends!

They may have liked traditional cuisine, but the Medicis were certainly gourmets. Caterina de Medici, daughter of Lorenzo II De Medici and great grand-daughter of Lorenzo “il Magnifico” (on a side note: she was also Queen of France) is a great example of that. Caterina was a true food lover and when she married, at the age of 14, Henry II Orléans and moved to Paris, she brought with her from Italy an ice cream maker from Urbino, three chefs, and, just in case, a bunch of pastry chefs. So great was her influence on the French court’s culinary habits that many consider her years in France as fundamental for the development of our neighbors’ national cuisine, to the point that quintessential French dishes, such as their famous onion soup, are in fact Tuscan in origin and were brought to Paris by Caterina’s chefs.

The young Queen apparently was very fond of artichokes stewed with chicken livers, herbs, butter, and olive oil, to the point she once got food poisoning from it. Even béchamel sauce was elaborated by her chefs when still in Italy and was then adopted by French experts.

The Later Middle Ages and the Renaissance in Rome and the Papal Court

More about the Italian Renaissance cuisine

Rome was the seat of one of the wealthiest, most luxurious of all courts, that of the Pope. The tendency we mentioned of honoring the Lord at the table was embraced with joy by the papal entourage: greed didn’t seem so much of a sin anymore to the eye of the rich and powerful of the eternal city. 16th and 17th-century sources speak of luscious banquets, with hundreds of different dishes served.

Music, dances, and singing were common entertainment during such feasts. The luxury and, let’s face it, excesses of Rome were common to other cities of the peninsula: the Serenissima, Venice, the Ferrara of the Este family, Milan and the Sforzas, all fought to achieve the highest levels of luxury and grandeur when it came to entertaining and, well, feed the rich and powerful of Europe, sometimes getting pretty ingenious and creative while doing it.

In 1513, for instance, Pope Leo X (of the Medici family) organized a banquet to celebrate his nephew Giuliano’s nomination to the Roman patrician. The table, set for twenty, selected guests, was placed on a stage in the very middle of Campidoglio’s square. The stage was surrounded by rows of seats for people to come and watch the show.

More of it in 1595, when Cardinal Grimani offered a banquet to representants of the city of Venice in Palazzo Venezia: guests were welcomed by the outlandish sounds of fifes and drums, which also accompanied the coming to the dining room of each dish and side: trumpets introduced preserves and jams, while gold and silver plates covered in cookies and pinenuts made their appearance on the delicate notes of harps.

The meal continued with a milk soup and dozens of roasted roes served on enormous trays. The majestic sounds of tubas followed an overwhelming display of 74 (yup, seventy-four!) large plates of chicken in Catalan sauce, whereas it was the mellow, refined harmonies of violas to create the chosen backdrop to roasted pheasants. Dessert was a concoction of whipped cream and marzipan, accompanied by performances by an exotic belly dancer, followed by a children’s choir. No mention of how long guests spent at the dinner table is made in official documents…

The Later Middle Ages and the Renaissance in the Cities of the North

Florence and Rome, of course, but we’d be mistaken to think that the towns and cities of the northern regions of Italy didn’t love their culinary excesses in the late Middle Ages and during the Renaissance. What more to learn about Italian Renaissance cuisine?

Cristoforo da Messisbugo, for instance, borne witness to the gastronomic adventures of the Estense court in Ferrara in a text called Banchetti, Composizione di Vivande et Apparecchio Generale (which roughly translates as “Banquets, the composition of dishes and a general view of the banquet’s setting”). Messisbugo is, in fact, a valuable witness, as he was a well-learned humanist and of a certain lineage, too, besides having been steward and chef in the Estes’ home. Thanks to his works, the court of Ferrara gained notoriety all over Europe as an artistic center, supported by the magnanimity of the Estes’ patronage.

Fulfilling their role of protectors and supporters of the arts, the Estes’ banquets had nothing to envy to an actual vernissage: when Ercole d’Este married the daughter of the King of France, in 1529, the climax of the celebrations was nothing less than a representation of Ludovico Ariosto‘s Cassaria. In case you forgot, good, old Ludovico is one of Italy’s most iconic and respected poets, known in particular for the epic poem L’Orlando Furioso.

But Messisbugo’s importance doesn’t only lie in having kept detailed track of the Estes’ banquets, but also of what was happening in their kitchen: as a chef, he described the typically northern Italian use of butter, as opposed to the olive oil-based recipes of Tuscany and the South.

Italian Renaissance cuisine

He’s been, moreover, one of the first chefs to pay visible attention to raw vegetables and delicatessen, and proved to be a connoisseur of both types of meat and fish, used equally in his recipes. Messisbugo was a pro also when it came to cooking methods: from frying to pickling, from stewing to grilling, there wasn’t a way to bake, cook and preserve he didn’t experiment with. He’s also one of the first to introduce heavily the use of filled pasta in his recipes.

Among his favorite ingredients, we find sugar, cinnamon, pinenuts, and raisins, a bow to a wholly Renaissance-like love for sweet and sour: let’s not forget the sugar, at that time, was only for the wealthy and so were recipes and dishes where it figured heavily.

If we speak of sugar, spices, and Renaissance cuisine, we must speak of Venice. La Serenissima had been holding the monopoly of sugar import and production since the age of the Crusades. The same could be said of oriental spices, of which Venice was an importer for the whole of Europe. Naturally, Venetian cuisine of the period was to be influenced by the city’s contracts with the East and its commercial role. A curiosity: so much was the name of Venice associated with sugar, that its use became a symbol of the city’s wealth. In 1574, on the occasion of Henry III’s visit, the king of France was welcomed by two hundred of the most beautiful noblewomen of Venice, all dressed in white and covered in jewels.

The tables of the banquet organized in his honor were adorned with sugar sculptures created by Sansovino, a well-known architect and sculptor of the time: two lions, a queen upon her horse with a tiger on each side, David and Saint Mark, patron of the city, surrounded by Popes, animals, and trees. All cutlery was made of sugar, just as of sugar were tablecloths and napkins, bread, and plates.

Renaissance chefs loved sugar, so. It’s no surprise, then, to discover that candied fruit –which is basically sliced or chopped fruit or fruit peel cooked in sugar syrup– became very popular in the Renaissance and became pretty much a staple for all the trendiest desserts of the time. Panettone and panforte, both rich in candied fruit and, today, symbols of traditional Italian baking, are children of the Renaissance just as Leonardo’s Mona Lisa.

The 16th century, we can really say, was a time of culinary excesses in large parts of Italy, an exception made, maybe, for Florence and the Medici, who favored a relatively sober display of wealth. However, it is easy to see how such a desire to impress and display large quantities of food came from a more or less unconscious need to exorcise the fear – always present and always real – of famines, epidemics, wars, and tragedies, which would have had hunger as their first result.

New flavors from the New World

The Discovery of America in 1492 marked an essential historical and cultural moment for Europe. Even though it didn’t happen straight away, it was also to influence profoundly the way we cooked and our tastes. New ingredients ended up on the table of the rich and powerful of Italy with relative ease, however, it was to take a much longer time for all people to enjoy the novelties and delicacies of the New World. One of the first New World’s things to appear on Italian “noble” tables was turkey. Apparently, the bird became so popular that even the Estes had a turkey breeding farm; they were also considered a particularly welcome wedding gift.

Turkeys aside, the first product to make it across the Atlantic ocean chronologically was sweetcorn. Cristoforo Colombo himself was said to have carried a handful of seeds in his pockets when he travelled back to Europe in 1493. About 40 years later, sweetcorn (called mais in Italy) was already one of the main coltures of Veneto, South Lombardia and, more in general, of the Po’s fertile plains, from where it reached the South.

Sweetcorn’s, as well as American beans’ cultures, were used when soil needed to “rest” in between others and helped to ameliorate its fertility. They both required little to grow and could be produced in large quantities, greatly helping to reduce the fear and incidence of famine in Europe. Interestingly enough, however, their diffusion halted after the first years of popularity: Europeans were reluctant to fully embrace the new products, and only in the 17th century both sweetcorn and beans finally entered at full speed the kitchens of Italy and Europe.

The same happened with another famous import from the Americas: the potato. Studied as a curiosity for years by botanists, it was adopted straight away in Spain and Italy, but it would become a staple of European cuisine only in the 1600s.

A different story is that of the ubiquitous tomato. Imported quickly from South America, some say it was quickly adopted by the Spaniards and, indeed, the Italians. It’s pretty safe to assume this is true for our Spanish cousins, to the point one of the earliest Italian recipes including tomatoes, dating from 1692, is for a sauce called pomodoro alla spagnola, that is, Spanish style tomatoes, which seems to point to an already well-established presence of the fruit on Spanish tables at that stage.

In Italy, tomatoes were considered more of a curiosity or a sort of magical ingredient for a pretty long time: in the 17th century, it was believed to be an aphrodisiac, so it was often used in love potions. Otherwise, for decades tomato plants were used only as a decoration. In Italy, so the story says, it entered the kitchens of the poor first, and that of the rest of the country only after Queen Margherita gave the thumbs up to a dish named after her, a dish that made our cuisine even more famous around the world, pizza…

The Italian Renaissance cuisine and the history of Italian cuisine in the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and its most amazing dishes still have secrets to be discovered. In the third part of our tale, we’ll get closer to our times and will find out more about the most prestigious traditional Italian gastronomic publications, as well as take a look at the culinary events that characterized the 20th century.

See also History of Italian food part 1, History of Italian food part 3 and History of Italian food part 4

Ariosto composed the poem “Orlando Furioso”. The author of the”Gerusalemme liberata” is Torquato Tasso.

Thank you Anonimo sorrentino for pointing that out. I edited it.