What happened in Italy during World War II? A quick historic overview of Italy World War 2 events and facts

Like many other people in Italy and around the world, I was grown up by my grandparents. They were all born between 1913 and 1918, they lived – and fought – the Second World War on their skin. They had different memories, as faith reserved them different events during those dark years. Regardless of what impact the war had on their lives, it changed them forever.

I also carry in my mind their memories of World War 2. Memories that were, to me as a child, fascinating stories. Stories of bombs deflagrating during the night and escapes towards shelters. Stories of life in the countryside, many families in a single farm, to keep safer from Allied bombings. Stories of young women alone with their children, missing their men, sent to the Italian front. Stories of youth, of laughter, of gentle German soldiers and not so gentle partisans. Stories of love and loss.

There would be a lot to say, about the lives of my grandparents during the years of the Second World War. There are enough words to fill the pages of a book! Yet, their stories, along with readings and books, will give an idea of how life was in Italy, during those faithful and tragic years. A quick overview of Italy’s world war 2 events.

Italy during World War II

Life in Italy during World War II didn’t differ much from that of other civilians around Europe. It was characterized by restrictions. Living under a dictatorship, such restrictions didn’t simply take the form of limited amounts of non-National goods, fuel, and even items of clothing, but also of censorship.

Freedom of speech had been severely cut since the very inception of the Fascist Regime, which was largely controlled through the Ministry of Propaganda. Just as it had been happening in Nazi Germany, it was controlled what Italians could say, write and know about the war and politics.

The letters written by soldiers from the front to their families, for instance, were always inspected by censorship officers. These would blank out in black ink anything deemed non-constructive for the Fascist Regime or that could affect public opinion negatively. The only correspondence free from censorship limitations was that entertained by members of the army.

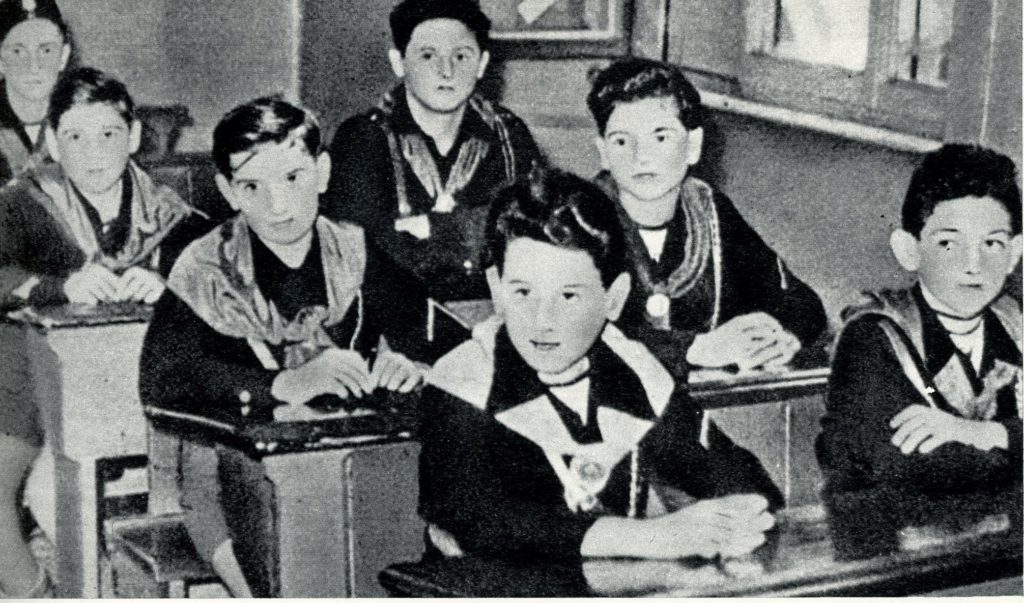

The Fascist propaganda machine worked throughout all sectors of society and embraced all ages. Since the 20s, children were enrolled in the Fascist Regime’s youth associations. Boys and girls between 6 and 8 were part of the Figli della Lupa (the she-wolf children).

From the age of 8 to 14, boys became Balilla and girls Piccole Italiane (little Italians). Then, from the age of 14 to 18 boys became Avanguardisti and girls Giovani Italiane (young Italians). At this stage, young women were considered ready to tackle their duties as wives and mothers. Fascism, like Nazism, had a very traditional view of womanhood, whereas boys enrolled in the Fasci Giovanili di Combattimento until the age of 22. At this age, they were considered ready to take up their role as defenders of the fatherland and become soldiers.

Food, metals and clothing in Italy in WW2

When Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935, the League of Nations immediately enforced an embargo against the country. This surely affected it, but not as much as the League probably had hoped, at least at the beginning.

Germany was already very close politically to the Fascists at this time, allowing Mussolini to maintain proficuous commercial relations.

In a way, the embargo strengthened Mussolini’s desire to make Italy an autarchic country. One that’s able to sustain itself and its economy only with products and produce coming from within its borders and from its colonies. Coffee for instance was largely substituted with chicory and tea with hibiscus flowers coming from the African colonial lands. We called it “carcadé” and it’s still a relatively popular drink in Italy, especially during the hottest months.

By the beginning of the war, in June 1940, the country was already struggling. Further restrictions were implemented, with heavy rationing of specific foods such as meats, butter, and cereals. Soldiers at the front were usually given larger rations of restricted foods than civilians. They even obtained things not available to people at home outside of the black market. My grandfather, who fought on the Russian front where he found his death at the age of 29. He used to send back home to grandma and their with two children, his own coffee and chocolate. This can be found in the content of some of his beautiful letters.

My maternal grandparents spent most of the war on the farm where my grandfather’s family worked as sharecroppers. They never really had problems with food, as grandma used to say. With a hint of pride, I remember – they never had to eat brown bread, as they could make their own white flour.

Keep in mind that World War 2’s brown bread had nothing to do with what we know today! It was largely made with chaff and, at times, it was made bulkier with sawdust. All rationed foodstuff, including bread, was given out by the State, by each family being allowed to keep a specific amount. Its quality, as you may imagine, was extremely low and plenty of people tried to get better food on the black market.

Truth is that things, from this point of view, were slightly simpler for those living in smaller, country villages or in the countryside. It was much harder for city dwellers. Fruits, vegetables, cereals, and meat were more easily available in the countryside, and they were often simply exchanged among families rather than bought. Of course, this didn’t mean life was easier, but simply not as bleak.

In an attempt to help people in cities, the Régime implemented orti di guerra, war’s orchards, destining large sections of city parks, and many a sports field to the cultivation of vegetables and cereals. In spite of it, people in large urban conglomerations endured extreme hardships.

The grandmother of our director, Paolo Nascimbeni, used to recollect how, during the Nazi presence in Rome, she would work as a cook for the German contingent. The food available for the occupiers (we’re talking about the months after the 8th of September 1943) was plentiful and included many sought-after items like meat and poultry.

When she had the opportunity, she would hide a steak in the rubbish, only to pick it up before going home, where she could cook it for her family. Like Paolo’s grandma, many women and men of those years used all types of stratagems to feed their children and loved ones. (**Note from Paolo: and I have to add that many years after World War II my grandmother kept in storage cases and cases of sugar and always tried to save on food. On the contrary, to most Italian grandmother she was not a good cook and my joke was telling her that she secretly worked for the resistance. )

Italians during World War 2 didn’t only have to make huge sacrifices in the kitchen. Metals were also needed to support the country’s war effort and citizens were asked to contribute by surrendering great amounts of items made in iron, including gates and fences. Also items as copper and tin, metals largely used to produce kitchenware and farm instruments.

The Products of Autarchy in Italy

Italy during World War II was characterized by autarchy, or autarchia as we say in Italian. This was an important part of Italy’s life and economy both before and during the war years. Through autarchy, Mussolini believed that Italy would not only have freed itself from economic dependence from other countries but would have also gained back pride in itself and its achievements.

The sanctions imposed by the League of Nations first and the war effort after didn’t only mean the country could no longer import goods from abroad but also severed its export ties with most of the world. This meant one side that there was an evident need to substitute goods once imported with local ones. Though, there was also a surplus of all those things Italy used to export. The two issues were solved by using plenty of the latter to produce the former.

Italy couldn’t export its cheeses, so it used the milk in excess for its caseine, from which a fiber called lanital was created. Lanital was similar to wool in texture and it helped to keep warm during the winter months. Cafioc was a cotton-like fiber obtained from hemp. The wine was used to produce alcohol and turned into a relatively efficient type of fuel. Wood coal was chosen instead of coal. Also, as I have mentioned, hibiscus flowers were brewed instead of tea and chicory instead of coffee. The rabbit was no longer solely used in the kitchen, but its fur became essential in the clothing industry too.

The symbol of the autarchic industry of Italy before and during the Second World War was orbace. Made with wool fibers treated in a particular way, orbace was strong and waterproof and for these reasons chosen to make uniforms for the Milizia Volontaria and the Camicie Nere.

Italy under the bombs in WW2

Since the beginning of the war Italy, like other European countries, was the victim of numerous airborne attacks. It wasn’t only cities to be in danger, but also specific locations of strategic relevance in the countryside. Those often seen as important logistic joints!

Shelters were identified or built-in cities and villages to guarantee some sort of safety to civilians. Still, many simply left urban conglomerations and sought refuge in the country, thinking to be safer there. The anti-bomb alarms rang at any time of day or night, creating a continuous sense of fear and instability in most. Electricity was rationed, which meant that nighttime was often a candle-lit affair for many. The fear of nighttime bombings got people into the habit of covering up their windows so that not even the flicker of a small flame could be seen from Allied airforces.

(Roberto Pani/Flickr)

Italy during World War II and people’s Lust for Life

Those of us who had the extreme fortune of growing up with the people who lived the war, however, know the magnitude of it failed to break them.

Throughout the many, many tales of war, my grandparents gave me a sense of the love of life, and the desire to enjoy it always shined through. Even my paternal grandmother, who lost her husband and was left a window at 24 with two young children to raise on her own, had fond moments of remembrance of her youth, at least until my grandad was around. Even if he was a soldier and spent very little time at home, she smiled at the thought of the beauty of their love, in spite of the tragedy and bleakness of their surroundings. My maternal grandparents were the same: youth, camaraderie, sense of belonging, and an immense eagerness to live a happy life in spite of it all, always transpired from their memories.

This generation, the generation that lived and fought the war, experienced on their own skin what the death of human nature truly means. They saw it, and it marked them for life. Yet, many of them, instead of mourning for what can only be defined as a global loss of faith in man’s nature, rose from tragedy with a true lust for life and for happiness, to be found in all things, even the small ones. This is one of the most important things learned through Italy World War 2’s events.

This is why I believe my grandparents taught me much more than tying my shoes and holding a spoon in my hand. They taught me the importance of finding happiness in everything, in spite of everything.

Francesca Bezzone

PS END of the war. The Americans arrive….. At the end of the war, when the allied were in Italy, chef Renato Gualandi had to cook for a dinner for allied generals and he came up with a sauce made out of available ingredients: spaghetti bacon, cream, processed cheese, and dried egg yolk, topped with a sprinkle of freshly ground pepper. He did not know at the time but he basically invented the carbonara pasta.

Well written article! Though I have a question why would a soldier be allowed to send his rations back home when that could have taken to fuel the army’s need?