Modern Music taking notes from the 17th Century

Since Renaissance times, music and science went hand in hand.

There was a family connection between music and science.

Galileo Galilei, the father of modern science, learned to apply mathematics to observable phenomenon from his father Vincenzo, who worked out the application of the inverse square law to the relationship between pitch and tension of vibrating strings. He was also a member of the Florentine Camerata, associated with the birth of opera, and is credited with the invention of secco recitative.

At the turn of the 17th century Vincenzo’s Camerata, looking for an alternative to the domination of words in the polyphony of the previous century, reached for inspiration back to the Greeks. In the old polyphonic style, but this had not been the case in polyphonic music in the 16th century. In the new style, the earliest examples of which are called monody, a new polarized relationship was created between all-important vocal melody and supporting harmonic ensemble. Music’s new role was to heighten the expression of the text. Recitative is the clearest example of this new texture.

The texts most often set in the new genre that would turn into opera were not at all new, however. On the contrary, often the texts for the monodies, and later the operas that employed the new style, were taken from Ovid’s Metamorphosis. This Roman poet’s collection of ancient Greek myths also provided the subjects for many of the frescos that decorated the walls of the villas of that time.

With the composition of operas like Monteverdi’s Orpheo, the sung word was supreme, at least in theory. However, it did not take many decades for the creation of new kinds of vocal and instrumental virtuosity, making use of the new musical textures in new contexts. Soon idiomatic sonatas were being composed for many instruments, while cantatas were opportunities for vocal fireworks. Even in the new genre, opera, by the middle of the 17th century the text soon became an excuse for vocal display.

Regardless of varying dominance of music and word, with the move towards a vigorously emotional musical expression, music’s harmony developed from modality to tonality. Within the 17th century what is today often called common practice harmony was established, although it took some more decades for it to be codified. It is this common harmonic practice that every popular musician uses to this day.

It was between the deaths of Galileo and Newton that the most famous Italian instrument makers Stradivari, Amati, and Guarnari worked.

The violin family predates the work of these famous makers by many decades, however. Shepardic Jewish musicians may have invented the viola in the early 16th century, probably used at first to substitute for the tenor in three part songs at the court of Isabella d’Este. These players, fleeing the inquisition in Spain, needed different tools for their new audience in Italy.

The rest of our bowed stringed instruments followed the viola: the violin (little viola) the violone, (big viola) and, at the beginning of the 18th century, finally the violoncello, (little big viola.) Some authorities claim that the other bowed stringed family, viola da gamba family, was invented at more or less the same time as the viola.

In the 16th century the social contexts of these two families, the violin and viola da gamba, were distinct. The viola da gamba was associated with the aristocracy and with serious polyphonic music; the violin was the brash shrill choice of the musician who eked out a living playing dances.

At the turn of the 17th century, the new musical sung staged versions of the Greek myths, the new operas, required a new instrumental accompaniment. To intensify further the heightened emotional atmosphere at these operas not just the new musical texture was created, but a new ensemble was assembled. This was the beginning of the orchestra, with the violin family as its backbone. The viola da gamba had only a minor role in the new orchestra, but its family continued to flourish for another 6 generations, until the sheer numbers and variety of activities associated with the violin overshadowed those of gamba, at least in the minds of writers on music.

These Italian musical genres, opera, sonatas, and cantatas, the instruments that figure in them, and the musicians that played them, were exported from the Italian states to all the countries of Europe, and to their colonies. So it was that Frescobaldi worked in Dresden, Geminiani in England and in Ireland, Ariosti in London, and countless other examples. And the violin soon made it to nearly every part of the globe. Durable, adaptable, it made its way into a rainbow of musical styles, outlasting many of its contemporaries, the harpsichord, lute, recorder, and many other unique and beautiful musical creations.

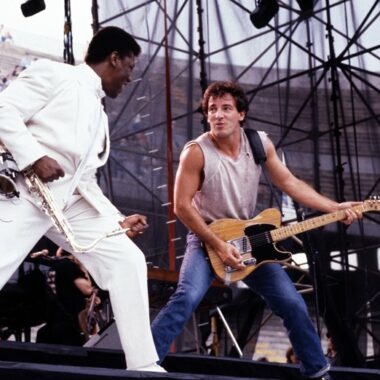

To this day kids learning classical music learn ‘forte’ for loud, ‘allegro’ for fast, ‘fine’ for end. All commercial music depends on the harmonic language first created for opera centuries ago. It is not too much to say that Britney Spears is still feeding on the harmony language created in the Italian Renaissance. Of course, Vincenzo Galilei would not have recognized her music, any more than Galileo would have recognized the Hubble telescope, or Stradivari would have recognized the Berg violin concerto. Nonetheless all these modern creations, in their different ways, depend on the achievements of the Renaissance Italian mind.

Thomas Georgi