The 19th century was a time of great change for Italy, as the modern world emerged, so it’s natural to wonder how was life in Italy during the 19th century. The most prominent events of this time revolve around the rise of the Italian unification movement known as the Risorgimento. It was the social and political process that eventually succeeded in the unification of Italy involving the many city-states that have been united in the modern country of Italy.

The exact dates of the beginning and end of the Risorgimento are unclear, but scholars believe it began at the end of the Napoleonic era, with the Congress of Vienna, in 1815. The process of the unification of Italy ended with the Franco–Prussian War in 1871.

History of Italy in the 19th Century

The Beginnings of Unification of Italy

The intellectual and social changes that were questioning traditional values and beliefs started in the late 18th century in Italy. The liberal ideas coming from other countries like Britain and France were spreading rapidly through the Italian peninsula. Vittorio Emmanuele II, the first king of Italy with his most notorious concubine Rosina were also supporting this movement.

The First War for the Italian Independence began with protests in Lombardy and revolts in Sicily. This resulted in four Italian republics creating constitutions in 1848. Pope Pius IX fled Rome and the Roman Republic was then proclaimed upon the arrival of Garibaldi. When Mazzini arrived in Rome, in March 1849, he was appointed Chief Minister of the new Republic.

In the meantime, King Charles Albert of Piedmont-Sardinia joined the war and attempted to drive the Austrians out of the country. It looked like the Italian unification timeline was near. Austrians however eventually managed to successfully defeat Charles Albert in the battle of Novara in 1849, slowing the country’s run towards independence. Victor Emmanuele II however managed to win the battles so he then became the first king after the unification of Italy.

Camillo Benso di Cavour

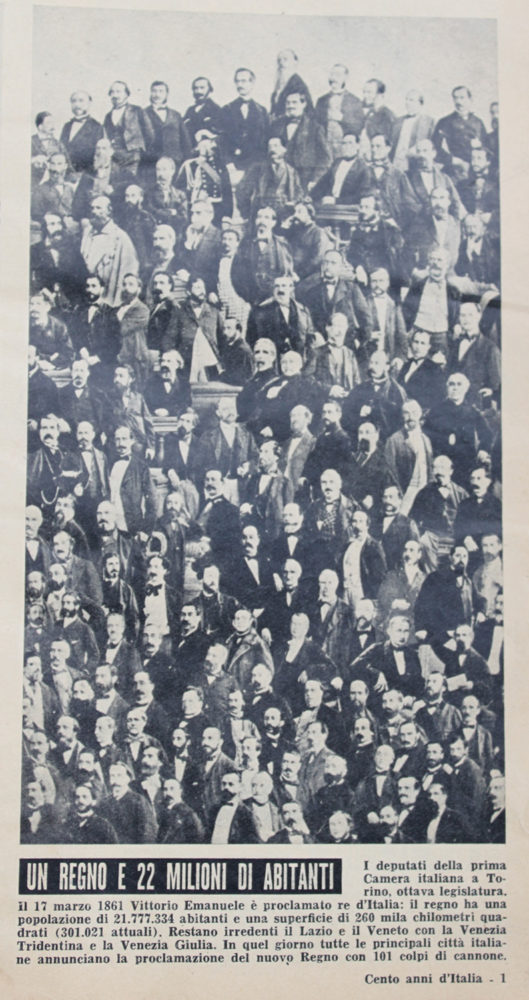

Count Camillo Benso di Cavour was to become the prime minister of the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia in 1852. It was only because of the count’s leadership and policies that the unification of Italy became possible!

Cavour persuaded Napoleon III of France to plan a secret war against Austria. Soon, a war on Italian soil against Austria began. The French troops helped Piedmont defeat Austria in two important battles at Solferino and Magenta. Austria was soon forced to surrender the region of Lombardy, along with the city of Milan, to Napoleon III. In 1859, Napoleon III then handed over the region of Lombardy to King Victor Emmanuel II.

Two years later, thanks to the troops of Giuseppe Garibaldi, the peninsula was unified under the Savoy crown. Turin became the first capital of the Kingdom of Italy; Rome was not to become part of unified Italy until 1870. As you can see, the Italian unification timeline was quite long with many different playgrounds.

Italian society in the 19th century

The Italians of the Risorgimento

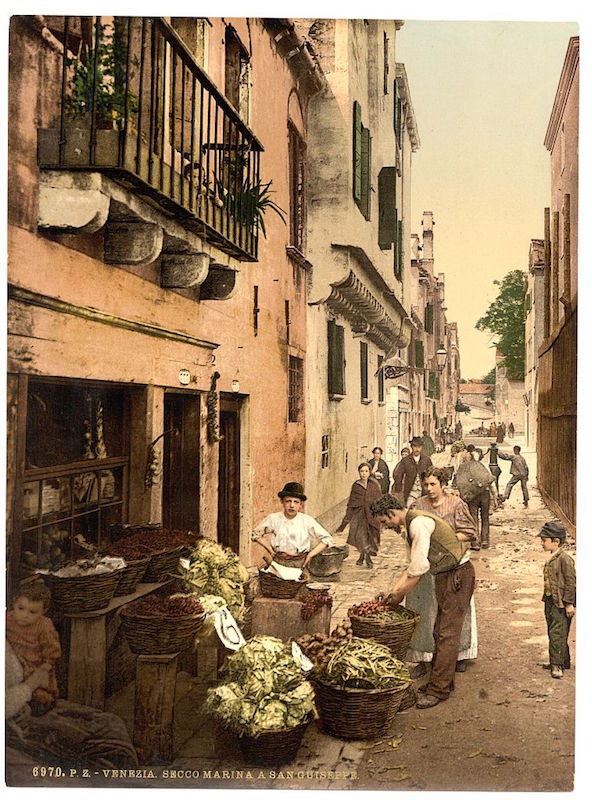

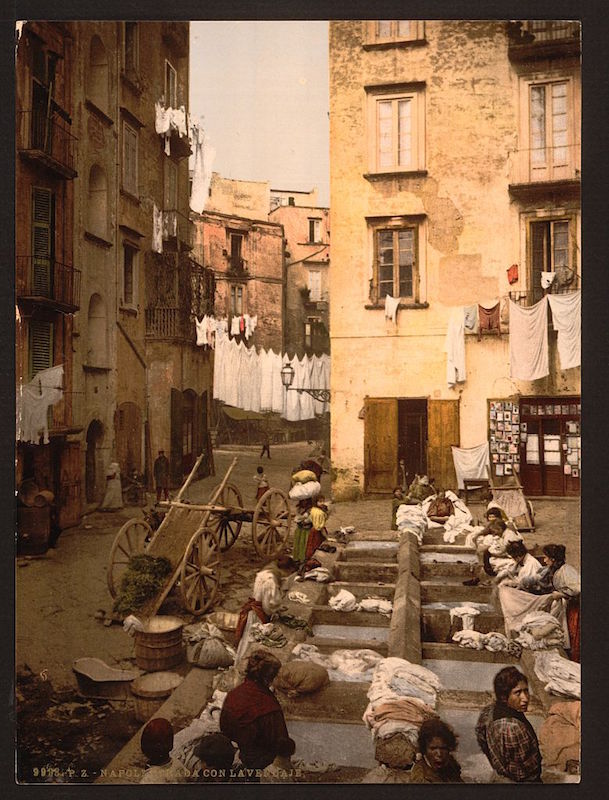

In many ways, the roots of several well-known aspects of Italian culture find their origin in the 19th century. The land, the food, and the people were all shaped by warfare, struggle, and the desire for independence. Most of the men who fought for freedom during this period were peasants, seeking a chance for something better. Northern Italy, mostly under the direct influence of Austria and the House of Savoy saw the emergence of industry; however, life was hard for most Italians, who remained poor.

Southern Italy fared worse than the North: neglect and the oppression of wealthy European landlords who exploited local peasants to tend their lands created the basis for the later Mafia organizations.

However, it is often through strife that humans are their most creative. This is most evident in the foods of Italy.

Food in Italy

The struggles of the 19th century saw the introduction of many of our favorite Italian foods. Greedy landowners of Northern Italy, decided long ago to feed their workers with cornmeal, which by now was to the North what pasta was to the South. Poverty made tomatoes, once thought poisonous, a staple of Southern Italian cooking. Pasta, already stable part of a typical southern kitchen, would never be the same.

In all areas of the country various wild plants, considered weeds by many, were incorporated into foods in times of want. However, as the 19th century went on, these traditional foods of the poor, became common among all classes.

Some, like the Pizza Margherita, became symbols of the newly created Kingdom of Italy. In 1891, Pellegrino Artusi, at age 71, completed the first Italian food cookbook.

Life in Italy during the 19th century: Italian Art

Italian music in the 19th century

The 19th century was the time of romantic opera, first initiated by the works of Gioacchino Rossini. However Italian music of the time of the Risorgimento was dominated by Giuseppe Verdi, one of the most influential opera composers of all times. Although modern scholarship has reduced his actual role in the movement of the unification of Italy, for all intents and purposes, the style of Verdi’s works lends itself to being the soundtrack to Risorgimento.

Toward the end of the 1800 ‘popular’ Italian music start appearing – The worldwide known ‘O Sole mio‘ was written in 1898.

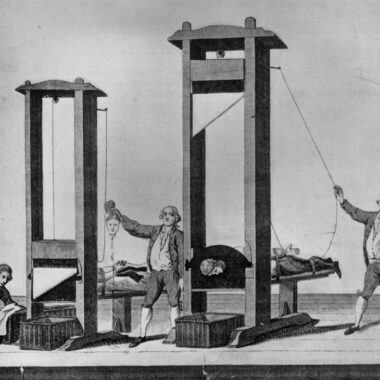

Pictures of Life in Italy in the 19th century

hi all of your stories sound interesting i need help with a project im working on about Italy does anyone know anything about the enlightenment of Italy i know im a year late

Cynthia

I would go on a online service life Fiverr or similar and see who can speak both languages and can do the translation.

Paolo

I have a journal written by an ancestor in 1786 -1830ish. It is in French and Italian. I want very badly to have it translated. The ancestor was a Waldensian and named Ribetto (which morphed into Ribet).

Any suggestions?

Yes, the original spelling of our name was GUASCONI, according to Giovanni’s marriage certificate his father, Erminigildo was a farmer. Do you know if it is any easier to get birth certificates in Italy now? and where would I start as I don’t speak the language. All I have to go on is his parents names and that he was born in Genoa Piedmont. Pretty vague I know.

Hello Phillip, no Guascoine doesn’t sound Italian, it must be French. Probably because of the links with France that you mention.

I am told that the spelling of our surname is also French. My Great Great Grandfather, Giovanni Battista Guasconi migrated to Australia in 1856. He married an Irish girl in 1869. On his marriage certificate it says he was born in Genoa Piedmont. The French did rule that part of Italy in earlier times. From what I can read there were crop failures and a lot of the northern Italian residents used to travel over the border into Switzerland but that was stopped with the closing of the border so there was no income. Also trade within the states on Italy was very low.

I am curious why my family has French DNA and no Italian. My family came from Castiglione Chiavarese in Liguria Genoa. I know the French took that area at one time. My family were farmers. My grandfather left Italy in 1885. My grandmother’s family was already in California. I read that there was a blight in the vineyards at that time. I am wondering if they left because they were of French descent? Maybe they left because their crops were failing? Our name is Antonini, so if we are French that is puzzling.

My ancestors had three children die in the month of March in 1831 in Camigliano. How can I found out if there was an influenza or cholera outbreak at that time? I can’t find an age for these children, but they were listed as bracciale. At what age would children start working in the fields?

I am researching for a novel and hope you can provide answers to a few questions. The setting is pre-WWII in Emilia, south of Modena in a rural area. The character is a landowner, owner of a large casa in a small town. I assume electricity would be possible. Also that the very rich might have a telephone but not many others would. How might the casa be heated? Money would be no object.Would it be possible to have a kerosene-fed stove (I picture a large ceramic one). I will appreciate any insight you can provide. Grazie.