Shortly after the crucifixion of Jesus, a small rag-tag group known as Christians began to make its mark in the heart of the old Roman Empire. Within the next few centuries this once highly persecuted religious sect became the official religion of Rome – effectively wiping out the old pagan faith. Since that time, emperors, popes, missionaries, crusaders and merchants have filled Italian churches with relics of martyrs and artifacts purportedly belonging to Jesus and the Apostles.

The relic trade was at its height in medieval Europe and Italian cities felt that having the remains of a popular saint in their church would not only give them powerful intercessional powers but also draw more pilgrims – and revenue to the area. Consequently, Italian cathedrals, monasteries and shrines are home to a bewildering number of relics – many connected to the Crucifixion and some with miraculous properties. Below is just a sample of the many holy relics found in churches and shrines throughout Italy.

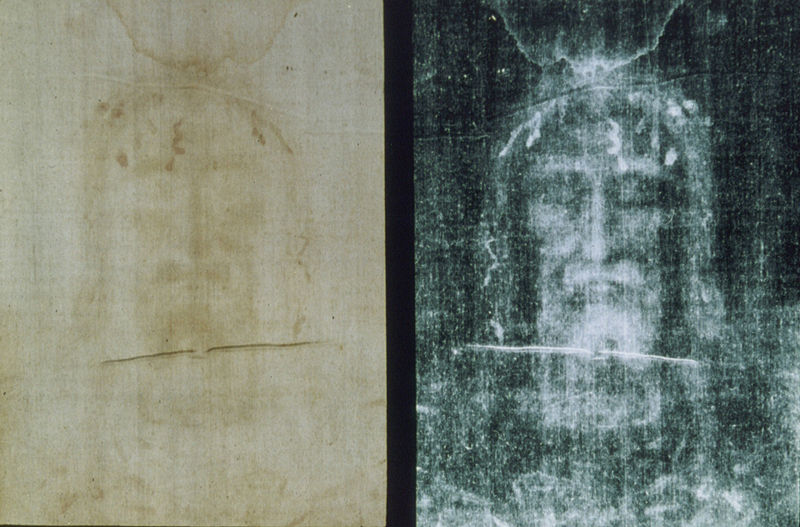

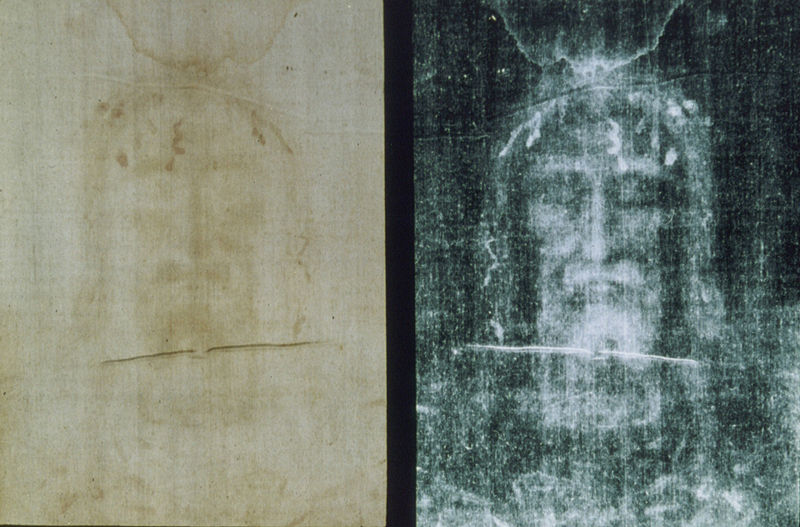

Shroud of Turin

Arguably the most famous of Italy’s holy relics is the enigmatic Shroud of Turin, located in Turin Cathedral. Tradition claims it as the burial cloth of Jesus but its subsequent history is hard to trace before the 14th century. It had been held as a family treasure by the House of Savoy for centuries, but was given to the Holy See in 1983. The image on the cloth acts as a photographic negative, a property that still defies explanation.

Holy Relics in Italy: The Shroud of Turin

Holy Relics in Italy: The Shroud of Turin

Even with modern technology, the repeated attempts at duplication by experts have fallen short. In 1988 the Shroud was radiocarbon dated, with the results suggesting a medieval origin. However, there have been criticisms of the carbon dating procedure including the possibility the carbon dating samples were corrupted due to the Shroud’s exposure to fire over the centuries. A recently popular theory has the Shroud being yet another masterpiece of Leonardo da Vinci using a technique known as a camera obscura. Regardless of how or when the image was created, the possibility of it being a forgery has not stopped worldwide interest from the skeptical and the faithful alike. The fact that the Shroud of Turin is on display about twice a century (the next being in 2025) adds to its mystery.

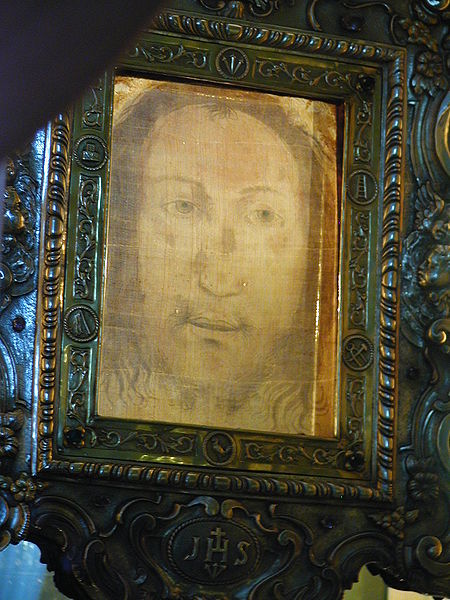

Volto Santo – Veil of Veronica

Not as well known but equally mysterious as the Holy Shroud is the Volto Santo, better known as the Veil of Veronica. According to apocryphal tradition, the Veil is said to be a miraculous image of the “True Face” of Jesus formed when Veronica of Jerusalem wiped Christ’s face as he carried the cross. There are several relics in Europe that claim to be the Volto Santo, including a rarely seen one in St. Peter’s in Rome that may have gone missing in the 16th century. However, what many believers feel is the authentic Veil has been in a Capuchin monastery in Manoppello since at least the 17th century and recently brought to light by Jesuit Father Heinrich Pfeiffer.

Holy Relics of Italy: The Volto Santo

Holy Relics of Italy: The Volto Santo

The Volto Santo is made of a very fine and expensive linen of ancient origin called byssus, made from the clinging filaments of shellfish. The Volto Santo looks like a portrait of a man with calm eyes, slightly open mouth and long hair. The face does not seem that realistic but how the image was created on such a material is yet unknown. The most mysterious aspect of the intriguing, virtually hypnotic image on the Volto Santo is that it seems to change expressions from serene to almost demonic depending upon how it is illuminated.

The Titulus Crucis of Santa Croce

The mother of Emperor Constantine, Saint Helena is credited with rediscovering many of Jerusalem’s Christian holy sites. One of the relics supposedly discovered by Saint Helena is the True Cross, which has subsequently been lost. However a piece of the headboard of the True Cross (known as the Titulus Crucis) may be housed in Rome.

The Basilica of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme was built by Saint Helena within the confines of a former imperial palace to house the relics of the Passion including pieces of the True Cross, nails from the Crucifixion and the Titulus Crucis. The relic is a small piece of wood with a portion of the inscription “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews” in Latin, Greek and Hebrew. Even though linguistic experts have stated that the inscriptions are very convincing, a recent carbon dating of the wooden relic has given a date of somewhere closer to the11th century AD. However, there is documentation of pilgrims visiting the Basilica to see the relics of the Passion before the Titulus Crucis was supposedly made. It is entirely possible that the original relic was lost or destroyed during the various sackings of Rome and that a medieval replacement was made to continue the Basilica’s title of a Pilgrim Church.

The Scala Santa

Holy Relics in Italy: The Scala Santa

Holy Relics in Italy: The Scala Santa

Saint Helena is also credited with discovering and bringing to Rome the white marble stairs of the governor’s palace of Jerusalem. Saint Helena believed these to be the same stairs that Jesus climbed during his Passion and so installed them in the Lateran Palace. The Scala Santa is covered by a wooden staircase with cutaways revealing what is said to be drops of the blood of Christ. This is one of the most popular attractions for religious pilgrims to Rome, who traverse the steps on their knees as an act of penance. Each of the 28 steps has an individual prayer, with penitents receiving a papal indulgence for each step completed. The Scala Santa may be more legend than fact but the faithful have found it a powerful symbol that has inspired replicas to be built worldwide.

Madonna della Civita

On a hill in the ancient town of Itri is a sanctuary dedicated to the Virgin Mary. However what separates this sanctuary from the hundreds of others found throughout Italy is the legend surrounding the central icon. Known as the Madonna della Civita, it is an image of the Madonna and infant Jesus supposedly painted by St. Luke the Evangelist.

The Madonna della Civita has been in Itri since at least the 12th century where local legend claims a mute cowherd discovered it while looking for a lost cow. Over the centuries the icon has survived many hardships including being hidden from the Germans in World War II as well as being struck by lightning. The painting has been heavily restored over the centuries, with little or none of the original image surviving.

A highly plausible theory is that the Madonna della Civita was originally an eastern icon that survived the Byzantine iconoclasm period of the 8th century and eventually found its way to Itri.

The Blood of San Gennaro

Every citizen of Naples is familiar with the religious mystery associated with San Gennaro (Saint Januarius) as it is directly tied to the city’s survival.

A glass phial of solidified blood is one of the relics of this 4th century Christian martyr, patron saint of Naples. Eighteen times a year the reliquary that holds the blood is taken out and held upside down, if the miracle happens and San Gennaro’s blood becomes liquid, Naples is once again safe from disaster.

In the past plague, earthquakes and even eruptions of Vesuvius have been predicted by the blood remaining solid – as recently as 1980. The blood of San Gennaro has not been thoroughly examined and similar properties have been duplicated by investigators, but the relic’s centuries of history heralding disaster for Naples remains unexplained.

By Justin Demetri

You could also be interested in

Saintly Relics of Italy part 1

Saintly Relics of Italy part 2