The history of Rome is closely tied to its military history. As a fledgling nation, Rome’s military was disorganized and sporadic, only being brought together as it became necessary. With time, however, the military would become a professional war machine, with its members fighting for the glory of the state, rather than for personal acclaim. The expansion and fall of the Roman Republic and the rise of Imperial Rome can all be attributed in part to shifts in military structure, loyalty, and purpose. A look at the history, practices, and composition of the Roman Army from the early Republic to the Roman Empire will follow.

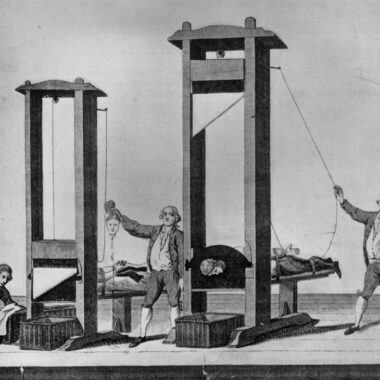

Roman military’s standards (Wikimedia)

Roman military’s standards (Wikimedia)The Early Roman Army

Starting with the traditional founding of Rome in 753 BCE, and continuing through the legendary reigns of the seven Kings of Rome, the Roman military consisted of a citizen army, an army of non-professional citizen soldiers who were drafted in times of war. Because these militias were only sporadically created as became necessary, these groups became known as legions (from legio, “levy”). Their primary weapons were everyday tools, items which served a practical purpose for civilians. Armor and specialized weapons, such as swords and spears, were only used by the wealthiest in the militia. This disorganized fighting system proved useless against the invading Etruscans from the north during the late 7th century BCE.

Having dominated pre-Republican Rome, the Etruscans drafted Romans into their armies, requiring that they use Etruscan military tactics. This system involved organizing soldiers on the basis of socioeconomic status. An individual in the half of the army with the highest standing became a heavy armored hoplite soldier, known as a Phalangarius for being trained in the traditional phalanx formation. The next lowest half among the remaining men was designated medium spearmen. The remaining individuals became light spearman (velites) or, in the case of the lowest classes, slingers and javelin-throwers used in skirmishes.

Even after the Etruscan reign was overthrown and the Republic was formed in 509 BCE, Roman legions continued to use the phalanx formation, despite its impracticality on the hilly terrain of Italy. Around 390 BCE, Gallic warriors moved down the Italian Peninsula, destroying the Roman army in their way. Rome was subsequently sacked by the Gauls, and suffered heavy losses. The people of Rome were forced to pay off the invaders to save their city. This defeat would bring about numerous military reforms, slowly shaping the Roman army into a conquering machine. In 225 BCE, almost two hundred years after the invasion of 390, a Gallic force of 50,000 infantry and 20,000 horsemen which had again moved down the Italian Peninsula was devastated by this new Republican army’s tactics and weaponry.

The Roman Army during the Republic

Troops were organized into small tent parties known as contubernium, which consisted of eight soldiers, which shared a tent, millstone, mule, and a cooking pot. A century was made up of ten of these tent parties, commanded by a centurion. With the military reforms of Camillus in the early 4th century BCE, a clear chain of command was established, with centurions of several grades and military tribunes, from the Equestrian class, who were in the military to advance their political careers. Camillus also introduced a new tactical unit, called the maniple (manipulus, “handful”), which was composed of 120 to 160 men (two centuries), and commanded by the senior of the two centurions.

During the middle republic, legions consisted of cavalry, light infantry, and heavy infantry, all of which were land owners who bought their own equipment, weapons, and armor. A legion’s cavalry, or equites, consisted of ten groups of thirty men on horseback, all commanded by one decurion. The cavalry consisted of wealthy young Romans looking for a stepping stone to an eventual political career, and as such, were unlikely to be seen near the front lines during battle. The light infantry consisted of javelin-throwers, and had no formal organization, being called into battle as necessary. The principal military unit of the legion was the heavy infantry, which included those individuals who could afford more expensive equipment, such as a bronze helmet, shield, armor, and a pilum, a heavy, short spear with a long metal shank. The weapon of choice of a heavy soldier was the gladius, a short sword.

The heavy infantry was subdivided into three groups, based on age and military experience. The hastati (“spearmen”) formed the front line during battle, and consisted of twelve hundred younger individuals. The second line of attack, known as principes, included twelve hundred men in their late twenties to early thirties (in their “prime”), with more experience than the hastati. The rarely-used third line, the triarii, consisted of six hundred older, veteran soldiers. These three lines were divided into maniples, which were spaced in a so-called quincunx formation (a modern term, referring to the checkerboard layout resembling the five dots on dice).

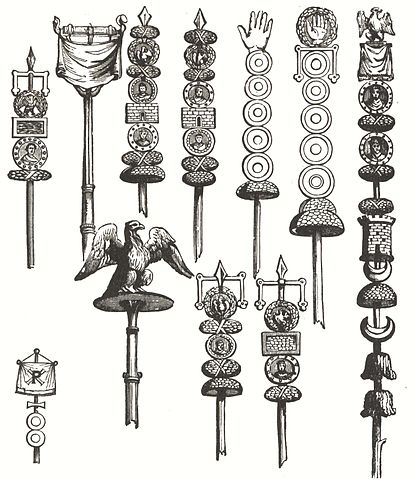

The Roman Eagle, a symbol of the city’s power and of its military, in a

The Roman Eagle, a symbol of the city’s power and of its military, in afunerary monument of Augustus’ times.

(wikimedia)

The legion as a whole advanced in these three lines behind a screen formed by the twelve hundred light infantry. In the first line, the hastati left gaps equal in size to their cross-sectional area between each maniple. The second line principes followed in a similar manner, lining up behind the gaps left by the first line. This was also done by the third line, standing behind the gaps in the second line.

Cavalry was placed along the sidelines to deflect any incoming enemy cavalry or light troops from the flanks. As the army approached its enemy, the velites in front would throw their javelins and retreat through the gaps in the lines. Once they had moved behind the first line, hastati from the rear of each maniple would move into the gap on their left, creating a solid line of soldiers. Right before impact with the enemy, the hastati threw their pila at the enemy, disorganizing them. (Not only was the pilum deadly, but it was designed to bend rather than break, and so would get stuck in enemy shields and hang there, weighing them down right before the impact of the attack). The hastati would then move in to attack with their short swords in close combat.

In the late Republic, the maniple would be reduced to an administrative unit, being replaced by the cohort (cohors) as the basic military unit within a legion. The cohort consisted of six to eight centuries, and was led by a single centurion with the help of an optio (“chosen one”), a private with special responsibilities and skills, including the ability to read and write. The most senior centurion in the legion, who also commanded the first cohort, was the primus pilus (“first spearman”). Below him in rank were the primi ordines from the first cohorts, followed by the centurions of each of the other cohorts: pilus prior and his deputy pilus posterior, princeps prior and his deputy princeps posterior, and hastatus prior with his deputy hastatus posterior.

During the late Republic, the reforms of the novus homo general Gaius Marius (157-86 BCE) greatly increased the size, loyalty, and skill of the Roman army. The cohort became endorsed as the official tactical unit. By discarding the three-line quincunx formation, legions became free to adapt to different conditions on the battlefield, including varying enemy formations.

Roman Soldiers in Turtle Formation

Roman Soldiers in Turtle Formation

The reform of Gaius Marius

After Marius, the state would supply the majority of equipment for troops, creating a more uniform, efficient military unit. Rather than have these supplies and equipment shipped to necessary, Marius had his troops carry the entire load, which for each individual weighed roughly sixty to ninety pounds. Troops would routinely march up to twenty miles in a day, but when they reached their destination, they were not allowed to rest. Instead, they had to build all the necessary forts and watchtowers before sleep could be had. A soldier burdened with these heavy loads thus became known as a Mulus Marianus (“Marius’s mule”). [4] As quoted of Virgil by Flavius Vegetius Renatus:

“The Roman soldiers, bred in war’s alarms,

Bending with unjust loads and heavy arms,

Cheerful their toilsome marches undergo,

And pitch their sudden camp before the foe.”

-(Flavius Vegetius Renatus. The Military Institutions of the Romans.)

The most effective of Marius’s reforms was the allowance for individuals of all classes to join the military, whether they owned land or not. This would maintain the large size of the army, made up of soldiers working fixed terms for relatively decent pay. By giving every soldier the option own a plot of land or a large sum of money upon retirement, Marius greatly increased the loyalty and morale of the troops.

These reforms, however, would lead to the end of the Republic. The lower classes, who resented the wastefulness of the wealthy, became the majority in the Roman army. Because of their status, the Senate refused them the promises made by their generals. Soldiers relied on generals such as Marius to divide up any acquired lands and loot among their legions. This shifted troop loyalty from the state to their commander, directly leading to the destruction of the Republic. Popular and successful generals such as Julius Caesar and Lucius Cornelius Sulla were effective at swaying military loyalty away from Rome.