Italian Baroque Composers: Tomaso Albinoni

Venice had become the cultural and artistic pearl of Europe by the mid seventeenth century and was the birthplace of composer extraordinaire Tomaso Giovanni Albinoni. June 14th, 1671 marked the entry of young Tomaso into the world as the eldest son of a wealthy paper merchant.

In stark contrast to other musicians of his era, Tomaso Albinoni did not pursue wealthy patrons to support the creation of his compositions, at least not until the death of his father in 1709. His father had left the running of his business to a younger brother, thereby relieving Tomaso of his familial duty while allowing him the financial stability to pursue his musical interests.

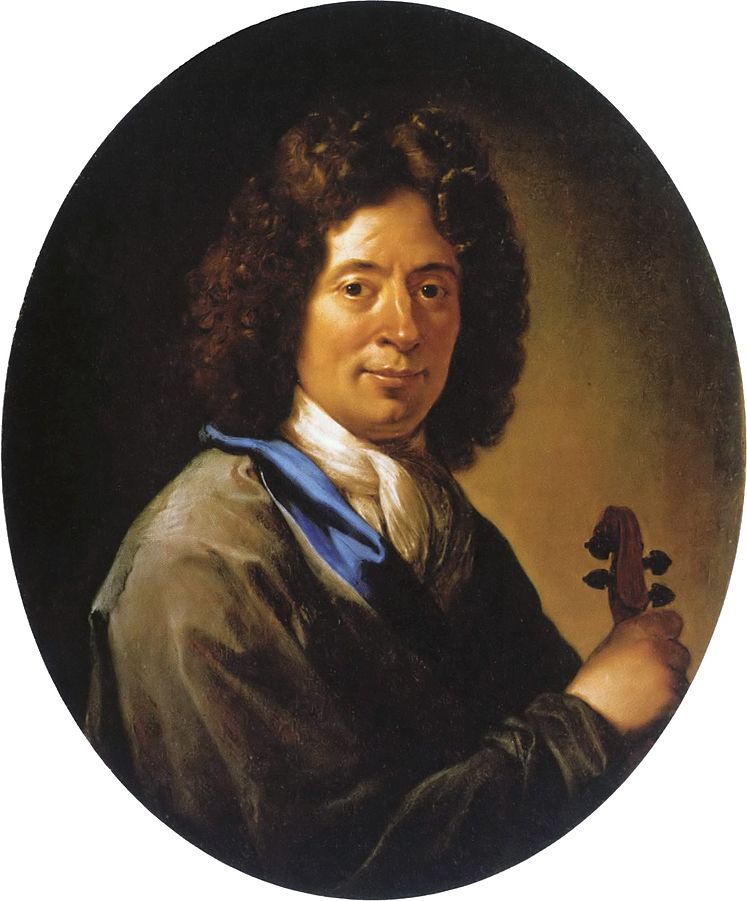

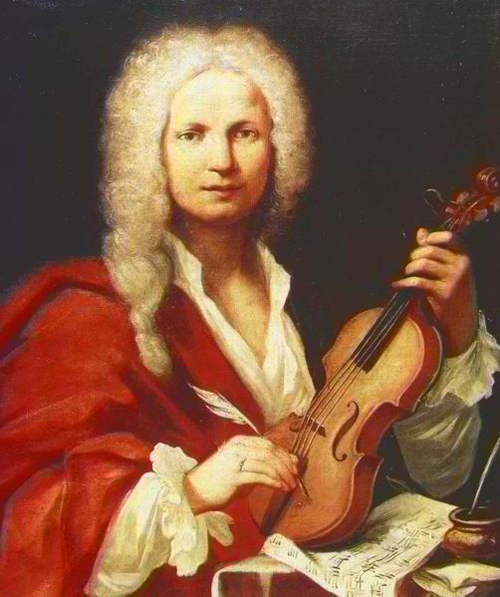

Nor did Albinoni need to work for the church as most of the great musicians of those years, such as Antonio Vivaldi – a fellow contemporary Venetian – and Arcangelo Corelli, but rather for himself. He claimed for himself the moniker “Dilettante Veneto”, interpreted as “Dedicated, Venetian Amateur”.

His earliest musical talents were displayed as a singer of notable ability and more so as a violinist. At this time in Venice, musical performers had to be members of the Musician’s Guild, otherwise they could not play publicly. As a result of this restriction, Albinoni turned to composition as a means of musical expression. One report has it that he also ran successfully an academy for singing.

Albinoni’s body of work contains approximately 81 operas, most of which have been lost to the ravages of time and war. His instrumental music has survived better and includes 99 sonatas, 59 concertos, and 9 sinfonias, all contributing to his being more widely recognized today for these compositions. Among his other musical accomplishments, Albinoni is credited with being the first Italian to write concertos that featured the oboe, a relatively new instrument at the time.

It is to the great misfortune of Baroque music lovers that much of what Albinoni composed, particularly after the mid-1720’s, is no longer in existence. A large collection of his written compositions had been housed in the Dresden State Library, which was destroyed in the Allied fire bombings of World War Two. Albinoni had been considered a prolific composer in his time, yet with the loss of this collection as well as other written pieces missing over time, the remaining body of his work is comparatively small. Also unfortunate is how much we don’t know about the man and his life after 1720s, the facts of which could offer posterity insight into the experiences that affected Albinoni and his music.

The one piece that Albinoni is most, and somewhat incorrectly, recognized for is the Adagio – a piece that has resurrected his name and music after many decades of virtual dormancy. The Adagio was created from a scrap of a document rescued from the ruins in Dresden by Italian musicologist Remo Giazzoto. Giazzoto was working on a biography of Albinoni and discovered six bars of melody and a bass line – all of the written original that survived. From that tiny fragment, Giazzoto interpreted the remainder of the piece, more or less writing the entire Adagio himself. It is likely that little of what we hear today, and for which modern music listeners most commonly associate Albinoni with, of the Adagio would resemble in any way the original piece as Albinoni had intended it to be heard.

Albinoni lived in Venice all his life, but took the opportunity to travel to important music centers throughout southern Europe. His extensive travels exposed him to other musical influences and the compositional works of fellow Baroque composers such as Handel, Corelli, and Vivaldi.

After the death of his wife Margherita Raimondi in 1721, Albinoni moved in with three of his eight children. Within a short span of time it is believed he withdrew entirely from public life, living as a virtual recluse. Physical ailments began to wrack his aging body and possibly included, among others, diabetes. His condition worsened and fever set in along with catarrh – an affliction that causes an inflammation of the nose and throat. On January 17th, 1751 at the considerably advanced age, in that era, of 79, Tomaso Albinoni died in the same city that saw his birth and much of his brilliant life, Venice.

Albinoni’s Adagio, directed by Von Karajan

By Bill Abbott