The last Italian ocean transatlantic was designed about 50 years ago. The Michelangelo liner, as it was named, housed the last descendant of the artist Michelangelo Buonarroti, from whom it inherited the name, on its debut trip.

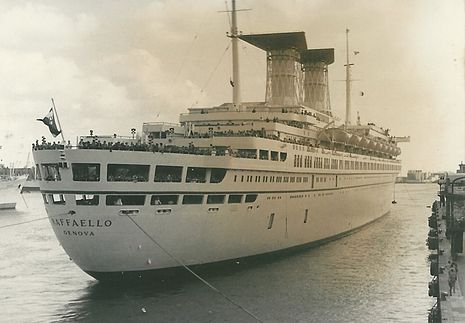

Today I’d like to tell you about the Italian fleet’s spearhead (together with its twin, Raffello) and its tragic fate. With a length of 275.8 meters and the most powerful turbo gearboxes of the time, it ruled the Atlantic Ocean for nearly a decade, particularly the Naples-New York route.

An Italian elegance icon

We are in the 1960s, and in Italy, we are attempting to leave the classic style that has graced the transatlantic rooms and halls (like Rex and Conte di Savoia). The architectural and artistic signatures are entirely Italian. Some competent architects who forged the Michelangelo were Nino Zoncada, Gustavo Pulitzer Finali, Italo Gamberini, Bino Bini, and Vincenzo Monaco.

The Italian spirit continues with paintings by Michelangelo and other current artists of the time, such as Gino Severini, Salvatore Fiume, and Giuseppe Santomaso, on the walls of the bow and the living rooms.

One of the many milestones broken by the transatlantic among its contemporaries is the 489-seat giant cinema-theater constructed by Roberto Gottardi and Marco Lavarello. On an Italian ocean liner, it was the largest theater ever erected.

If you enjoy Italian cinema, you will enjoy this gem. Some portions of the film Amore mio aiutami with Alberto Sordi were shot aboard the ship in 1969!

The first departure

The transatlantic Michelangelo was delivered to the Società Italiana Navigazione on April 21, 1965, and its first transatlantic journey, lasting seven days, took place on April 30, 1965. Everything went swimmingly, and the 1100 passengers returned to Genoa, where the ship was accessible to the public for the entire day.

The Michelangelo on the road

The Ansaldo project, which was in charge of the construction of both Michelangelo and Raffello, proposed a motion that was instantly recognized as extraordinarily complex. Even if the initial interest in the two twin ships seemed to augur well, the migratory flow via liners did not appear to be able to withstand the rivalry of the more well-known airplanes. The two most elegant ocean ships ever conceived took shape in this setting, yet they did not get the luck they deserved.

Early years on the Atlantic Ocean

The public’s enthusiasm for the transatlantic was at an all-time high throughout these years. So much so that the first berth in New York, May 20, 1965, was declared Michelangelo’s Day to mark the Italian liner’s initial arrival. Before sailing back to Genoa, the ship made a one-day stop at Pier 90 in New York, attracting 15,000 tourists.

There were some terrible memories on board the yacht, so it wasn’t all gold and glitter. Michelangelo encountered harsh weather conditions on April 7, 1966. At 10:20 a.m. on April 12, the ship was hit by a large wave, which broke through the bridge glass. Two passengers and a waiter were killed, while other crew members and passengers were seriously injured.

The initial excitement faded rapidly

The Michelangelo liner had a significant flaw: it housed classes (first class, economy class, and cabin class), but no common areas for passengers. Furthermore, several cabins lacked portholes. These were just a few of the reasons why Michelangelo’s initial enthusiasm waned. To compensate for the subsequent economic losses, the two sister ships began to be deployed on Caribbean trips in pursuit of better fortune. The crew’s strong opposition did not help the maritime sector, causing continual delays in departures of up to 48 hours, driving away even more tourists. The situation was escalating, and the Michelangelo was practically sinking.

To lift morale, and be the last to be tossed, the Società Italiana Navigazione altered the transatlantic journey schedule. Twenty-four-day trips, including one to the Arctic Circle, were financed. However, it was insufficient.

The end of an era

The new decade has only brought complications to the transatlantic relationship. Alitalia began flying the powerful Boeing 747 between Rome and New York in 1970, offering fares that were a third lower than the previous year.

The Michelangelo had to overcome additional challenges, and it lacked the necessary materials. The government issued the disarmament order for the transatlantic by July 5, 1975. Its final Italian journey sailed on June 25 on the New York-Genoa route, and it was laid up upon arrival.

The Iranian government paid 30 billion and 600 million lire for the ocean liner in October 1976, including all restoration costs. On July 8, 1977, it arrived in Bandar Abbas, Iran, for his final journey. With the start of the civil war and the strengthening of the political front, the Michelangelo was repeatedly robbed and partially damaged, culminating in his demolition in 1991.

This was the tragic and brief life of one of Italy’s most legendary ships.